Submission to the College of Physicians and Surgeons of

Saskatchewan

(5 June, 2015)

Re: Conscientious Refusal

(as revised)

Appendix "A"

Ontario College briefing materials

Full Text

A1. Introduction

A1.1 The Council of the College of Physicians and

Surgeons of Ontario (CPSO) was provided with a briefing note by the working

group that drafted Professional Obligations and Human Rights. The

briefing note helped to convince the Council to approve the policy.

A1.2 However, a review of the briefing materials shows

them to be deficient, erroneous and seriously misleading. Moreover, it

appears to have been physically impossible for the working group to have

considered the results of the second public consultation before preparing

the briefing materials.

A1.3 This suggests that the Saskatchewan College

Council should give little weight to the CPSO briefing note and not rely

upon the information it provides without independently verifying it, if

possible.

A2. Citation of Conscientious Refusal (CR No.1)

A2.1 One of the reasons offered by the working group to

justify the policy, including a requirement for compulsory referral, was

that it aligned with "the position taken by the College of Physicians and

Surgeons of Saskatchewan (CPSS) in their draft policy titled Conscientious

Refusal" and had been "approved in principle by the CPSS Council."

A2.2 This was clearly premature, since Conscientious

Refusal no longer aligns with the Ontario policy, and the withdrawal of the

requirement for referral supports the view that the CPSO requirement of

"effective referral" is unacceptable. (III.1)

A3. Reasonable apprehension of bias

A3.1 The Christian Medical and Dental Society and the

Canadian Federation of Catholic Physicians' Societies have filed an

application in the Ontario Superior Court of Justice asking for an

injunction against enforcement of the CPSO policy, Professional

Obligations and Human Rights.1

A3.2 According to the application, the CPSO

acknowledged that it had received 15,977 submissions during the second

consultation concerning the policy, which ended on 20 February, 2015. The

great majority of submissions opposed the policy.

A3.3 While the consultation ended on 20 February, a

working group wrote the final version of the policy by 11 February, at least

nine days before the consultation closed. This is one of the

factors that gives rise to concern about what the CMDS application calls

either "actual bias" or "a reasonable apprehension of bias" on the part of

the working group.

A3.4 On this point, the statistics provided by the CPSO

are of interest.

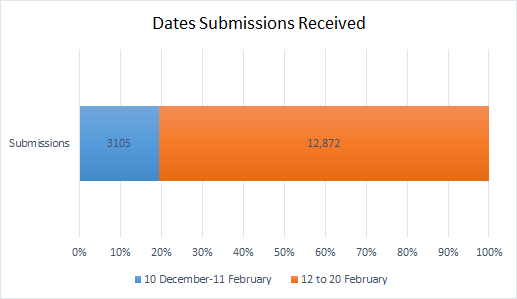

A3.5 According to the briefing note supplied to the

College Council,2 by 11 February, 2015

the College had received 3,105 submissions. This means that 12,872

submissions were received from 12 to 20 February inclusive. In other words,

over 80% of the submissions in the second consultation were received

after the final version of the policy had been written.

A3.6 Moreover, allowing sufficient time to receive

feedback is only the beginning. Having received them, one would expect that

a working group seriously interested in feedback would allow sufficient time

to review and analyse the submissions.

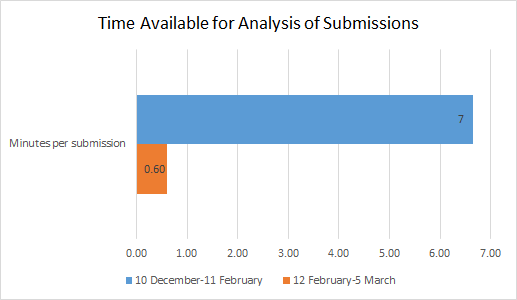

A3.7 During the 64 days of consultation ending 11

February, the College received an average of almost 50 submissions per day.

There were 43 working days during that period. Assuming someone spent eight

full hours every working day reading the submissions, it would have taken

one person about seven minutes to review each one.

A3.8 However, the College received an average of one

submission every minute of every hour of the last nine days of consultation

ending 20 February. With 16 working days available from 12 February to 5

March inclusive, the day before the Council meeting, one person reading

eight hours a day would have had no more than 36 seconds to review each

submission.

A3.9 This demonstrates that it is highly unlikely that

the CPSO briefing note can be safely relied upon by the Saskatchewan

College.

A4. Tunnel Vision at the College of Physicians*

A4.1 The College of Physicians and Surgeons of Ontario

has adopted a policy requiring physicians who have moral or ethical

objections to a procedure to make an "effective referral" of patients to a

colleague who will provide it, or to an agency that will arrange for it.3

In 2008, amidst great controversy,4 the

Australian state of Victoria passed an abortion law with a similar

provision.5

A4.2 After the law passed, a Melbourne physician,

morally opposed to abortion, publicly announced that he had refused to

provide an abortion referral for a patient. This effectively challenged the

government and medical regulator to prosecute or discipline him. They did

not. The law notwithstanding, no one dared prosecute him for refusing to

help a woman 19 weeks pregnant obtain an abortion because she and her

husband wanted a boy, not a girl.

A4.3 They obtained the abortion without the assistance

of the objecting physician,6 and they

could have done the same in Ontario. College Council member Dr. Wayne

Spotswood, himself an abortion provider, told Council that everyone 15 or 16

years old knows that anyone refused an abortion by one doctor "can walk down

the street" to obtain the procedure elsewhere.7

A4.4 So why did the College working group that drafted

the demand for "effective referral" urge College Council to adopt a policy

that so clearly has the potential to make the College look ridiculous?

A4.5 Moreover, why did the working group push for a

policy of "effective referral" despite having no evidence that even a single

person in Ontario has ever been unable to access medical services because of

conscientious objection by a physician?8

A4.6 Why did the working group supply Council with

deficient, erroneous and seriously misleading briefing materials9

- falsely implying, for example, that the Australian Medical Association

supports "effective referral" by objecting physicians?10

A4.7 Having selected the American Medical Association

for purposes of policy comparison, why did the working group fail to cite

any AMA policy document in its December briefing materials,11

and then, in March, leave out12 the fact

that AMA policy does not require "effective referral"?13

If AMA policy was relevant in 2014, why was it irrelevant in 2015?

A4.8 College consultation policy states that it "does

not review any content of any feedback for accuracy."14

Why, then, did the working group intervene in the second public consultation

discussion forum, trying to stifle contributors' criticism by offering a

purportedly 'correct' interpretation of the policy?15

A4.9 Why did the working group make final revisions to

the draft policy nine days before the second public consultation

closed, dismissing opposition that was overwhelming even then?16

A4.10 Four months elapsed between the end of the first

public consultation and the working group's first report and recommendations

to Council.17 In contrast, Council was

asked to pass the policy two weeks after the close of the second

consultation. Why the rush?18

A4.11 And why did the working group wait until the day

before the meeting to supply Council members with an explanation of the new

policy?19 Why has it not, even yet,

published a report of the second on-line survey like that provided during

the first?

A4.12. Lack of knowledge, lack of foresight, poor

judgement, poor research, human error and carelessness might explain these

problems, but for one disturbing fact. Almost every one of the errors,

omissions, and deficiencies and every active intervention or decision made

by the working group favoured its "effective referral" policy.

A4.13 What we seem to have here is not merely a series

of unfortunate events, but a pattern of conduct strongly suggestive of a

narrow and fixed ideological bias.

A4.14 Why such an impractical policy? Why insist upon

it when there is no evidence to support it? Why the deficiencies, errors and

misleading statements? Why finalize the policy nine days before the

consultation ended? Why call for an immediate decision about a controversial

policy affecting fundamental freedoms, without time for reflection - without

even a complete accounting of the second consultation?

A4.15 The most cogent answer is that the working group,

if not blinded by ideological extremism, had an exceptionally bad case of

tunnel vision.

A4.16 Tunnel vision explains why the working group

thought it a concession to allow a physician to refer a woman seeking a

sex-selective abortion to an "agency" that would arrange for it rather than

a physician who would provide it.

A4.17 Exceptionally bad tunnel vision accounts for the

suggestion by the chairman of the working group and the president of the

College that doctors opposed to abortion can avoid compromising their

beliefs by sending patients with unwanted pregnancies to abortion clinics.20

A4.18 But there is yet no satisfactory explanation for

the policy's central message: that ethical medical practice requires

physicians to do what they believe to be unethical. Even the worst

imaginable case of tunnel vision cannot account for that kind of incoherent

authoritarianism.

A4.19 The working group failed to provide any evidence

that the suppression of fundamental freedoms entailed by Professional

Obligations and Human Rights was justified, and that no less

restrictive means were available to achieve the legitimate objectives of the

College. Despite this - and without seriously considering any of the

foregoing questions - College Council approved the policy. If this is not

the best possible example of blind faith by institutional decision makers,

it will do until a better one comes along.

A4.20 Having failed to consider these questions before

approving Professional Obligations and Human Rights, it appears

that College Council will soon have the opportunity to consider them again.

Indeed, the Council may be compelled to answer them - not in the closely

controlled and congenial environment of its own offices, but in open court

during a lawsuit launched by the Christian Medical Dental Society. That will

likely be the beginning of a long trek to the Supreme Court of Canada, one

that could have been avoided had College Council properly discharged its

responsibilities.

A4.21 Certainly, the College is obliged "to protect and

serve the public interest."21 But the

public interest is served by civility, restraint, tolerance, accommodation

of divergent views and respect for fundamental freedoms. That requires

broad-mindedness and evidence-based decision-making, not tunnel vision and

blind faith.

*This appeared as an op-ed column in the

National Post on 13 April, 2015. It is reproduced here in

numbered paragraphs, with the notes not published with the column.

Notes

1. Ontario Superior Court of Justice, Between the

Christian Medical and Dental Society of Canada et al and College of Physicians

and Surgeons of Ontario,

Notice of

Application, 20 March, 2015. Court File 15-63717 ()

2. Salte BE.

Memorandum

to Council re: Draft Policy- Conscientious Objection, 23 March,

2015 (CPSS No. 75/15) p. 4-11.

3. College of Physicians and Surgeons of Ontario,

Professional Obligations and Human Rights (Accessed

2015-03-22)

4.

Letter from Dr. Mark Hobart to Mr. Edward O'Donohue, Chairperson, Scrutiny

of Acts and Regulation Committee, Parliament of Victoria, dated 7 June,

2011. (Accessed 2015-02-19).

5. Murphy S.

"State of Victoria, Australia

demands referral, performance of abortions: Abortion Law Reform Act 2008."

Protection of Conscience Project

6. Rolfe P.

"Melbourne doctor's abortion stance may be punished." Herald Sun,

28 April, 2013 (Accessed 2015-02-19); Devine M.

"Doctor risks his career after refusing abortion referral." Herald Sun,

5 October, 2013 (Accessed 2015-02-19).

7. Swan M.

"UPDATED: Ontario doctors must refer for abortions, says College of

Physicians." The Catholic Register, 6 March, 2015 (Accessed

2015-03-10).

8. Protection of Conscience Project, Submission

to the College of Physicians and Surgeons of Ontario Re: Professional

Obligations and Human Rights (20 February, 2015),

Appendix

"D".

9. Protection of Conscience Project, Submission

to the College of Physicians and Surgeons of Ontario Re: Professional

Obligations and Human Rights (20 February, 2015),

Appendix

"B": Unreliability of Jurisdictional Review by College Working Group.

10. Protection of Conscience Project, Submission

to the College of Physicians and Surgeons of Ontario Re: Professional

Obligations and Human Rights (20 February, 2015),

Appendix "B": Unreliability of Jurisdictional Review by College Working

Group- BII.3 (Australia)

11. It quoted a single sentence referring

generally to AMA policy from an article about conscientious objection among

pharmacists. Protection of Conscience Project Submission to the College of

Physicians and Surgeons of Ontario Re: Professional Obligations and Human

Rights (20 February, 2015),

Appendix "B": Unreliability of Jurisdictional Review by College Working

Group- BII.5.1 (USA)

12. Council Briefing Note-

Topic: Professional Obligations and Human Rights- Consultation Report and

Revised Draft Policy (March, 2015). In Meeting of Council, March 6,

2015, p 60-67(Accessed 2015-03-23).

13.

Letter from the AMA Council of Ethical and Judicial Affairs to the College

of Physicians and Surgeons of Ontario, 18 February, 2015 (Accessed

2015-03-23)

14. College of Physicians and Surgeons of

Ontario,

The Consultation Process and Posting Guidelines. (Accessed

2015-03-22).

15. Murphy S.

"A watchdog in need of a leash." Protection of Conscience Project

Blog, 3 February, 2015.

16. College of Physicians and Surgeons of

Ontario,

Meeting of Council 6 March, 2015, p. 61. (Accessed 2015-03-23)

17. The first consultation closed on 5 August,

2014. The meeting occurred 4-5 December, 2014.

18. The second consultation closed 20 February,

2015. Council was asked to pass the policy on 6 March, 2015.

19. Swan M.

"UPDATED: Ontario doctors must refer for abortions, says College of

Physicians." The Catholic Register, 6 March, 2015 (Accessed

2015-03-10).

20. Weatherbe S.

"Doctors who oppose abortion should leave family medicine: Ontario College

of Physicians." LifeSite News, 19 December, 2014 (Accessed

2015-02-26).

21. College of Physicians and Surgeons of

Ontario, About the College:

Self Regulation and the Practice of Medicine (Accessed 2015-03-22)

Prev | Next