Good News and Bad News

Presentation to the Catholic Physicians' Guild of Vancouver

North

Vancouver B.C. (22 November, 2014)

Full Text

Introduction

Thank you for inviting me to speak this evening. I have never been asked

to give a three hour presentation to a group of physicians. You will be

relieved to know that I have not been asked to do that tonight.

Those of you who saw the BC Catholic headline may have been expecting a

"lecture on medical ethics," but, thanks to Dr. Bright's introduction, you

now know that I am an administrator, not an ethicist, and that my topic is

freedom of conscience in health care.

Protection of Conscience Project

The Protection of Conscience Project will be 15 years old this December.

Although a meeting sponsored by the Catholic Physicians Guild provided the

impetus for its formation, the Project is a non-denominational initiative,

not a Catholic enterprise. Thus, if I mention the Catholic Church or

Catholic teaching tonight, it will be as an outsider, as it were, though an

outsider with inside information.

One more thing: the Project does not take a position on the acceptability

of morally contested procedures like abortion, contraception or euthanasia:

not even on torture. The focus is exclusively on freedom of conscience.

Context

The context for my presentation is provided by the passage of the Quebec

euthanasia law1 and the pending decision in Carter

v. Canada in the

Supreme Court.2 Physicians are now confronted by the

prospect that laws against euthanasia and physician assisted suicide will be

struck down or changed. If that happens, what does the future hold for

Catholic physicians and others who share your beliefs?

The context for my presentation is provided by the passage of the Quebec

euthanasia law1 and the pending decision in Carter

v. Canada in the

Supreme Court.2 Physicians are now confronted by the

prospect that laws against euthanasia and physician assisted suicide will be

struck down or changed. If that happens, what does the future hold for

Catholic physicians and others who share your beliefs?

Will you be forced to participate in suicide or euthanasia?

If you refuse, will you be disadvantaged, discriminated against,

disciplined, sued or fired?

Will you be forced out of your specialty or

profession, or forced to emigrate if you wish to continue in it?

What about those who come after you? If you avoid all of these

difficulties, will they?

In sum, will freedom of conscience and religion

for health care workers be protected if assisted suicide and euthanasia are

legalized?

These questions and the issues and problems they raise have been largely

avoided or glossed over.

They have been avoided by opponents of assisted suicide and

euthanasia because, understandably, they don't want to compromise their

central message: don't do it.

They have been glossed over by advocates of assisted suicide and

euthanasia because they are afraid that support for legalization may

evaporate if people think that unwilling physicians will be forced to kill

patients. Instead, they adopt a reassuring posture of respect for freedom of

conscience and tolerance for opposing views.

I will suggest tonight that we have reached the point at which these

questions and the problems they bring with them can no longer be avoided,

nor can they be glossed over with saccharine promises of respect and

tolerance.

Carter v. Canada

The common law that came to Canada from England recognized that suicide

can be deliberately chosen by someone who is of sound mind, but viewed such

acts as always immoral and contrary to reason.3 Deliberate choice was

understood to make suicide more wrongful, not less. Consistent with this

tradition, many people - Catholic physicians among them - continue to

believe that suicide, while not blameworthy if it results from mental or

emotional disorder, is immoral or unethical if deliberately chosen, should

always be prevented, and should never, ever be encouraged or assisted.

However, the ruling of Madame Justice Smith in Carter v. Canada

was based on a radically different fundamental premise. She held that

suicide is not always wrong: that it can, in some circumstances, be a

rational and moral act.4 In other words, she believed that it can sometimes

be a good thing to commit suicide. Logically, if it is good to commit

suicide in some circumstances, it must, in those circumstances, be good to

assist with suicide.5

However, the ruling of Madame Justice Smith in Carter v. Canada

was based on a radically different fundamental premise. She held that

suicide is not always wrong: that it can, in some circumstances, be a

rational and moral act.4 In other words, she believed that it can sometimes

be a good thing to commit suicide. Logically, if it is good to commit

suicide in some circumstances, it must, in those circumstances, be good to

assist with suicide.5

Granted this, it must also be a good thing, in those circumstances, to do

for someone like Gloria Taylor what she wants to do but is unable to do: to

end her life - to kill her. Thus, the judge's reasoning moved logically from

approving suicide, to approving assisted suicide, and then to approving

euthanasia.

According to Madame Justice Smith, the purpose of the law is not to

prevent all suicides or all assisted suicides. The sole purpose of the law

is to protect vulnerable people, who, in moments of weakness, might be

tempted to kill themselves without sufficient reason and reflection.6 Having

established this, she framed the key questions.

Can vulnerable people be adequately protected only by the absolute

prohibition of assisted suicide?

Or is there a less drastic alternative that can achieve the same goal?

The burden was on the defendant governments to prove that vulnerable

people cannot not be protected by anything less than absolute prohibition.7

They produced evidence of risk, which the judge accepted.8 However, the

effect of this evidence was significantly diminished because the judge

defined the goal as one of managing or reducing risk - not eliminating it

altogether.9 She concluded that the risks could be reduced to acceptable

levels.10

I suggest that her belief that suicide could sometimes be a good thing

led her to adopt the policy of risk management. I suggest she would not have

been so inclined in the case of something she believed to be always gravely

immoral. For example, if the subject were sexual assault, I doubt that she

would recommend risk reduction rather than risk elimination. I don't think

she would attempt to calculate an acceptable level of risk for rape.

For these reasons, I suggest that the trial court ruling in Carter hinged

entirely upon the foundational premise that killing oneself can sometimes be

a good thing. The premise was not challenged during the trial. Instead, the

defence of the law depended largely upon utilitarian arguments about the

ineffectiveness of safeguards, the risks to vulnerable people and slippery

slopes.

Now, I don't mean to denigrate those who did their best to defend the

law. In the first place, I am tackling this from a different perspective.

Moreover, the defendant governments probably believed - with good reason -

that moral arguments would be abruptly dismissed, with contempt or

condescension. However, keeping silent about morality does not produce a

morally neutral judicial forum. It simply allows the judge's moral beliefs

to set the parameters for argument and adjudication.

This applies not only in courtrooms, but in the public square.

This was illustrated during CBC's Cross Country Checkup following the

Carter decision.11 Most of those who opposed the ruling argued, as the

defendant governments did at trial, that assisted suicide and euthanasia

should not be legalized because that would endanger vulnerable people.

This was illustrated during CBC's Cross Country Checkup following the

Carter decision.11 Most of those who opposed the ruling argued, as the

defendant governments did at trial, that assisted suicide and euthanasia

should not be legalized because that would endanger vulnerable people.

But when asked if they would deprive Gloria Taylor of the right to

physician-assisted suicide, every one of them avoided the question. Not one

said that she should be denied help to kill herself.

They had argued against legalizing assisted suicide solely because of the

risk that vulnerable people would be exploited, and no safeguards could

adequately protect them. But Gloria Taylor could not plausibly be described

as a vulnerable and exploited person in need of protection, so they could

not explain why, in her case, assisted suicide should not be permitted.

And if they could offer no reason to deny it to her, upon what basis

would they deny it to others similarly situated? And what reason would they

have to refuse to help her kill herself?

Had they argued from the outset

against suicide and euthanasia on moral, philosophical or religious grounds

(though not excluding others), they might have been able to answer

differently. But, like the government defendants, they did not do so, and

were placed in a very awkward spot by the interviewer.

As you might be by a patient if the law is changed. In the case of

conscientious objection, silence about one's moral, religious or

philosophical beliefs is impossible.

Rights claims

Once suicide, assisted

suicide and euthanasia are understood to be benefits, it is possible to

assert that one has a right to them, at least in defined circumstances. The

Quebec euthanasia law purports to enact such a right,12 and the BC Civil

Liberties Association and others claim such a right in Carter.13 Such claims

imply that, in some circumstances, physicians have a legal or professional

obligation to kill a patient or to help a patient kill himself.

A statement by new CMA President, Dr. Chris Simpson, can be understood to

support that view. Responding to a suggestion that someone other than

physicians should provide euthanasia and assisted suicide, he said, "I don't

think we want to be reneging on our responsibilities to serve our patients."14

That is the language of obligation.

The obligation to kill

I want to dwell for a moment on the obligation to kill, but I should

first clarify my use of the term. I use "killing" in the sense explained by

Beauchamp and Childress in the Principles of Biomedical Ethics:

The term killing does not necessarily entail a

wrongful act or a crime, and the rule

'Do not kill' is not an absolute rule.

Standard justifications of killing, such as killing in self-defense, killing

to rescue a person endangered by another persons' wrongful acts, and killing

by misadventure. . . prevent us from prejudging an action as wrong merely

because it is killing.15

With that out of the way, I want to focus on the obligation to kill

because I don't think the nature of the obligation is sufficiently

appreciated. An obligation to kill must be distinguished from an

authorization to kill or a justification of killing.

Soldiers and police are legally authorized to kill, and all of us may be

legally justified in killing in self-defence. But neither the authority to

kill nor legal justifications for killing amount to an obligation to kill.

If the first shot merely wounds a bank robber, a policeman is not entitled

to administer a coup-de-grâce. There is no obligation to kill even in

military combat; deliberately killing disabled enemies is a crime.16

Soldiers and police are legally authorized to kill, and all of us may be

legally justified in killing in self-defence. But neither the authority to

kill nor legal justifications for killing amount to an obligation to kill.

If the first shot merely wounds a bank robber, a policeman is not entitled

to administer a coup-de-grâce. There is no obligation to kill even in

military combat; deliberately killing disabled enemies is a crime.16

Once we realize that an obligation to kill is not imposed even upon

people whose duties may entail killing, we can recognize that imposing an

obligation to kill upon physicians would be unique and extraordinary.

But it is not unprecedented.

An obligation to kill was formerly imposed on public executioners. The

essence of that obligation was captured by Blackstone's explanation that

"if, upon judgment to be hanged by the neck till he is dead, the criminal be

not thoroughly killed, but revives, the sheriff must hang him again."17

That is what an obligation to kill would require of a physician. If a

lethal injection failed to kill a patient, a physician would have to inject

the patient again to ensure that he is "thoroughly killed." This is implied

in the Quebec euthanasia law, which requires a physician who administers a

lethal substance to remain with the patient "until death ensues."18

It would thus seem to be difficult to legalize physician-assisted suicide

without also legalizing euthanasia.

Let's suppose a patient seeks assisted suicide to avoid being

incapacitated by a progressive illness. A physician provides the lethal

drug. The patient takes it, but doesn't die. Instead, the drug causes

precisely the kind of incapacitation that the patient wanted to avoid. It

could be argued that the physician who contracted to help the patient kill

himself is obliged to fulfil the terms of the contract: to make sure that a

patient who survives assisted suicide is "thoroughly killed" by euthanasia.

It seems likely that euthanasia will be wanted at least as a backup for

failed assisted suicide, as abortion is wanted as a backup for failed

contraception.19

Good news

Now, my reference to public executioners may be thought inappropriate.

I'll grant that it may cause discomfort, but I think it is instructive with

respect to the nature of the obligation to kill. But Catholic physicians and

others who share your beliefs are looking for assurance that they will not

be expected to kill patients if the Supreme Court strikes down the law. On

this point, there is good news and bad news.

The good news begins with some statistics. These are only approximations,

but they will do for present purposes. (See

Appendix "A")

Belgium

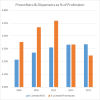

Euthanasia has been legal in Belgium since 2002, but the number of

physicians directly involved is quite low: I estimate a maximum of 0.62% to

2.3% of all Belgian doctors. The actual number of physicians directly

involved could be much lower. For example, one physician killed 28 patients

in about ten years, which, in official statistics, would be reflected as the

work of 28 physicians, not one.

Euthanasia has been legal in Belgium since 2002, but the number of

physicians directly involved is quite low: I estimate a maximum of 0.62% to

2.3% of all Belgian doctors. The actual number of physicians directly

involved could be much lower. For example, one physician killed 28 patients

in about ten years, which, in official statistics, would be reflected as the

work of 28 physicians, not one.

Netherlands

In the Netherlands, physicians may provide both euthanasia and assisted

suicide. Dutch General practitioners are the main providers: over 28% of

GP's were directly involved in 2011. But, of all Dutch physicians, it seems

that a maximum of 9% to 12% have been directly involved in reported

euthanasia.

In the Netherlands, physicians may provide both euthanasia and assisted

suicide. Dutch General practitioners are the main providers: over 28% of

GP's were directly involved in 2011. But, of all Dutch physicians, it seems

that a maximum of 9% to 12% have been directly involved in reported

euthanasia.

Taking the opposite view, this indicates that over 80% of Dutch GP's and

88% to 98% of Belgian and Dutch physicians overall are not directly involved

in killing patients. This estimate seems so high as to be improbable, until

we look at the numbers from Oregon and Washington.

Oregon and Washington

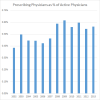

In Oregon, where assisted suicide has been legal since 1997, between

0.38% to 0.62% of the state's active registered physicians wrote

prescriptions for lethal medication between 2002 and 2013. The state of

Washington legalized assisted suicide in 2009. The number of Washington

physicians prescribing lethal medications has increased steadily since then

: from 0.21% to 0.34% of licensed physicians.

In Oregon, where assisted suicide has been legal since 1997, between

0.38% to 0.62% of the state's active registered physicians wrote

prescriptions for lethal medication between 2002 and 2013. The state of

Washington legalized assisted suicide in 2009. The number of Washington

physicians prescribing lethal medications has increased steadily since then

: from 0.21% to 0.34% of licensed physicians.

I repeat that these are only approximations, but I believe that they

demonstrate that if you refuse to kill patients or assist in consultations

leading to euthanasia or assisted suicide, your practices will reflect the

professional norm. From your perspective, I think that is good news.

I repeat that these are only approximations, but I believe that they

demonstrate that if you refuse to kill patients or assist in consultations

leading to euthanasia or assisted suicide, your practices will reflect the

professional norm. From your perspective, I think that is good news.

We

find more good news by turning once more to Carter and the Quebec euthanasia

law.

Carter v. Canada

In her ruling in Carter, Madame Justice Smith noted that the plaintiffs

did not assert that physicians should be compelled to provide euthanasia or

assist in suicide.21 Lawyer Joseph Arvay opposed the Project's intervention in

the Carter appeal because his clients had never argued that physicians

should be forced to kill patients,22 and, in his oral submission, said, "[N]o

one is suggesting that a physician who has a religious objection to

assisting a patient with his or her death must do so."23

Quebec euthanasia law

Quebec intervened in the Carter appeal to advocate for its euthanasia

law. When asked about the law's protection for conscientious objectors,

Quebec's lawyer said the law "allows a doctor to refuse to administer aid in

dying" and that physicians would "never [be] compelled to act against their

conscience."24 The Quebec Association for the Right to Die with Dignity had

previously assured Quebec legislators that it had no intention of forcing

physicians to provide euthanasia.25

Canadian Medical Association

Finally, the Canadian Medical Association's intervention in Carter

referred to the motion supporting "the right of all physicians. . . to

follow their consciences when deciding whether or not" to provide assisted

suicide or euthanasia.26 The CMA insisted that the law should protect both

physicians providing the procedures and those who do not.27

[N]o physician should be compelled to participate in

or provide medical aid in dying to a patient, either at all, because the

physician conscientiously objects . . . or in individual cases, in which the

physician makes a clinical assessment that the patient's decision is

contrary to the patient's best interests.28

There you have it. If you refuse to kill patients for reasons of

conscience, your refusal be consistent with the practice of an overwhelming

majority of physicians. Moreover, you have the solemn promises of euthanasia

activists and the Quebec government, made publicly before a legislative

committee and the Supreme Court of Canada, that you will never be forced to

do so. Finally, you have the support of the Canadian Medical Association,

underwritten by their intervention in Carter.

There you have the good news.

The bad news

On the one hand, the Quebec government and the plaintiffs in the Carter

case are asking the Supreme Court to declare that patients have a

constitutional right to physician assisted suicide and euthanasia. On the

other, we know that most physicians do not kill their patients or help them

kill themselves.

This has the makings of a first class train wreck.

If the Supreme Court strikes down the law, how can the Quebec government,

Mr. Arvay and the BC Civil Liberties Association ensure that patients will

be able to access euthanasia and assisted suicide without breaking their

promise that objecting physicians will not have to kill patients?

The answer is that they will keep their promises - to the letter.

Mandatory referral implicit in Carter

You will not have to kill. That will not be expected. But you will be

expected to cooperate. If, for reasons of conscience or religion, you won't

kill a patient or help him to kill himself, you will not have to. All you

will have to do is help the patient find someone who will. They promised

that you would not have to kill. They did not promise that you would not

have to find someone else to do it. This has been in the cards from the

beginning. That's why the Project joined the Catholic Civil Rights League

and Faith and Freedom Alliance as an intervener in Carter.

An obligation to at least facilitate euthanasia and assisted suicide was

implicit in Mr. Arvay's factum.29 It was implicit in his notice of claim30 and

in the testimony of his witness, Professor Margaret Battin. She implied that

a physician's refusal to provide assisted suicide or euthanasia

would amount

to unethical abandonment of patients.31 Mr. Arvay introduced into evidence32 a

report by a Royal Society panel of experts. It stated that if religious or

moral conscience prevents health professionals from killing patients or

assisting in suicide, "they are duty bound to refer their patients to a

health care professional who will."33 One of the authors of the report was

Professor Jocelyn Downie of Dalhousie University. Professor Downie helped

prepare Mr. Arvay's expert witnesses for the trial.34

would amount

to unethical abandonment of patients.31 Mr. Arvay introduced into evidence32 a

report by a Royal Society panel of experts. It stated that if religious or

moral conscience prevents health professionals from killing patients or

assisting in suicide, "they are duty bound to refer their patients to a

health care professional who will."33 One of the authors of the report was

Professor Jocelyn Downie of Dalhousie University. Professor Downie helped

prepare Mr. Arvay's expert witnesses for the trial.34

Mandatory referral implicit in Quebec euthanasia law

An undetermined number of physicians who don't want to kill patients or

assist with suicide may, in fact, be willing to refer patients to colleagues

who will. The Protection of Conscience Project won't hear from them. But

many physicians will not be willing to refer patients because they believe

that helping to arrange a killing makes them a participant in it. This was

very succinctly explained by the President and Director General of Quebec's

Collège des médecins, Dr. Charles Bernard. He said,

[I]f you have a conscientious objection and it is you

who must undertake to find someone who will do it, at this time, your

conscientious objection is [nullified]. It is as if you did it anyway. /

[Original French] Parce que, si on a une objection de conscience puis c'est

nous qui doive faire la démarche pour trouver la personne qui va le faire, à

ce moment-là , notre objection de conscience ne s'applique plus.

C'est comme si on le faisait quand même.35

This is a striking admission, because it is an indictment of Dr.

Bernard's own Code of Ethics. The Collège des médecins

Code of Ethics

requires that physicians unwilling to provide a service for reasons of

conscience "offer to help the patient find another physician."36

This is a striking admission, because it is an indictment of Dr.

Bernard's own Code of Ethics. The Collège des médecins

Code of Ethics

requires that physicians unwilling to provide a service for reasons of

conscience "offer to help the patient find another physician."36

Quebec's euthanasia law allows physicians to refuse to kill patients, but

adds that they "must nevertheless ensure that continuity of care . . . in

accordance with their code of ethics"37 - and that demands referral.

This is what Quebec's lawyer left out when he told the Supreme Court that

physicians would "never [be] compelled to act against their conscience." The

Project's lawyer drew the contradiction to the attention of the Court, using

it as an example of "precisely the sort of thinking that, in our submission,

ought to be protected against."38

Canadian Medical Association and mandatory referral

Much more could be said on that score, but let's look more closely at the

Canadian Medical Association's intervention. The Association's factum

stated, "[N]o physician should be compelled to participate in or provide"

the services. Surely this means that the CMA will support physicians who

refuse to help patients find someone to kill them.

Not necessarily. The devil is in the footnotes.

The factum states that "no jurisdiction that has legalized medical aid in

dying compels physician participation."39

However, the footnote to this comment includes a citation of the Quebec

euthanasia law, which, as we have just seen, is less than satisfactory. The

factum continues:

If the attending physician declines to participate,

every jurisdiction that has legalized medical aid in dying has adopted a

process for eligible patients to be transferred to a participating

physician.40

Here the footnote cites an addendum, "Schedule A," part of a package

prepared for the August AGM.41 Schedule A states that objecting physicians in

Washington, Vermont, Oregon, Belgium, and Luxembourg "have a duty to

transfer patient care to another physician who can fulfil the request."42

Here the footnote cites an addendum, "Schedule A," part of a package

prepared for the August AGM.41 Schedule A states that objecting physicians in

Washington, Vermont, Oregon, Belgium, and Luxembourg "have a duty to

transfer patient care to another physician who can fulfil the request."42

This is erroneous, misleading and troubling.

It is erroneous because the law in Vermont says nothing of the sort: in

fact, says nothing at all about this.43

It is misleading because it could be taken to mean that the objecting

physician has a duty to initiate the transfer to a willing colleague. This

is not required in any of the jurisdictions listed. All that is required is

that objecting physicians transfer the patient's medical records as

requested by the patient.44

So, erroneous and misleading.

It is troubling for two reasons

- First: the error and slant in the presentation favours the view that

failure to initiate a referral or transfer for euthanasia constitutes

patient abandonment.

- Second: I have had access to a document that indicates that this is the

view of influential CMA staffers..

I will not be more specific because I do not burn my sources, but I do

not think that sloppy research and clumsy draftsmanship adequately account

for the wording of Schedule A.

More direct evidence is available in the Association's oral submission.

This referred only to the need to avoid "overriding the consciences of those

who object to performing" euthanasia or assisted suicide and to respect "the

choice of those who do not wish to perform the practice."45

These

statements certainly do not engender confidence that the Canadian Medical

Association will support physicians who refuse to help patients find someone

to kill them.

So what did the CMA mean when it said "no physician should be compelled

to participate in or provide" euthanasia or assisted suicide?

I don't know. It all depends upon what the Association means by

"participate." I'm not a member of the CMA, but, if I were, I would make it

my business to find out.

What the future holds

Now, if the Supreme Court strikes down the law, an undetermined number of

physicians and health care workers will eventually begin to kill patients,

in the belief that what they were doing is not only legal, but morally

acceptable. In a sense, this would not be remarkable, because that sort of

thing has happened in the past, and it is happening now, in Belgium, the

Netherlands and Luxembourg, for example.

Nonetheless, many physicians and health care workers will, despite the

ruling, continue to consider euthanasia to be (morally) planned and

deliberate homicide. They will likely refuse to kill patients and refuse to

encourage or facilitate the killing of patients by counselling, referral or

other means.

And then the Collège des médecins du Québec, the Royal Society of Canada,

Professor Downie, and the BC Civil Liberties Association and others will

play the mandatory referral card. They will demand that health care

professionals be compelled to facilitate the killing of patients by referral

and other means.

How can I be sure of this?

Because some of them are already making these demands, and all of them

have been rehearsing this play for years. The last full-scale dress

rehearsal was in Ottawa. Three of your colleagues played starring roles.

Dress rehearsal in Ottawa

The play opened in January, when a 25 year old woman was unable to get a

prescription for birth control pills at an Ottawa walk-in clinic. The

physician on duty was a Catholic with an NFP only practice. The receptionist

gave the woman a letterexplaining that he did not prescribe or refer for

contraceptives for reasons of "medical judgment as well as professional

ethical concerns and religious values." She obtained the prescription at a

clinic two minutes away.46

The play opened in January, when a 25 year old woman was unable to get a

prescription for birth control pills at an Ottawa walk-in clinic. The

physician on duty was a Catholic with an NFP only practice. The receptionist

gave the woman a letterexplaining that he did not prescribe or refer for

contraceptives for reasons of "medical judgment as well as professional

ethical concerns and religious values." She obtained the prescription at a

clinic two minutes away.46

The physician was not forced to do something

contrary to his medical judgement and religious beliefs, and the young woman

obtained birth control pills by driving around the block. In more tolerant

times and places this might have been considered a successful compromise. In

this case, it sparked a witch hunt. Two more NFP only physicians - both

Catholics - were discovered lurking in the nation's capital.

The

three NFP only physicians account for 0.076% of about 4,000 physicians

practising in the Ottawa area,47 so at least potentially, 99.9% of Ottawa area

physicians are willing to prescribe contraceptives.

Nonetheless, a venomous feeding frenzy erupted on Facebook. News that

three out of 4,000 area physicians did not prescribe The Pill made

headlines.48 It was front page news and a public scandal that three Ottawa

physicians would not recommend, facilitate or do what they believed to be

immoral, unethical, or harmful. Consulted by an Ottawa Citizen columnist,

officials from the CMA and the CPSO seemed unsure about whether or not there

is room for that kind of integrity in the medical profession.49 A few days

later, a reporter with the Medical Post expressed doubt that it was even

legal.50 It eventually became the subject of a province-wide CBC Radio

programme.51

This was a wildly disproportionate response to news that a young woman

had to drive around the block to get birth control pills.

Why do I call this a rehearsal for confrontations about assisted suicide

and euthanasia?

A duty to refer patients to be killed

Because the arguments said to justify compelling objecting physicians to

provide or refer for contraception and abortion are the same arguments used

to try to compel objecting physicians to provide or facilitate euthanasia

and assisted suicide. I won't attempt to cover them tonight, but I will give

you a single example that demonstrates the connection.

In 2006 Jocelyn Downie was one of two law professors who wrote a guest

editorial in the Canadian Medical Association Journal claiming that

physicians who refuse to provide abortions for reasons of conscience had an

ethical and legal obligation to refer patients to someone who

would.52 Five

years later she was a member of the "expert panel" of the Royal Society of

Canada that, as we have seen, recommended that health care professionals who

object to killing patients should be compelled to refer patients to someone

who would.53 The experts argued that, because it is agreed that we can compel

objecting health care professionals to refer for "reproductive health

services," we are justified in forcing them to refer for euthanasia.54

Jocelyn Downie and Daniel Weinstock, another member of the Royal Society

expert panel, are members of the faculty of the "Conscience Research Group."56

This is a quarter-million dollar Canadian Institutes of Health Research

(CIHR) funded project.57 It is headed by Professor Carolyn McLeod and

supported by a research assistant and seven graduate students. A central

goal of the group is to entrench in medical practice a duty to refer for or

otherwise facilitate contraception, abortion and other "reproductive health"

services. From the perspective of many objecting physicians, this amounts to

imposing a duty to do what they believe to be wrong.

But that is just what the Conscience Research Group and others propose:

that the state or a profession can impose upon physicians a duty to do what

they believe to be wrong - even if it is killing someone - even if they

believe it to be murder - and that they should be punished if they refuse.

Killing is not surprising; even murder is not surprising. But to hold

that the state or a profession can, in justice, compel an unwilling soul to

commit or even to facilitate what he sees as murder, and justly punish or

penalize him for refusing to do so - to make that claim is extraordinary,

and extraordinarily dangerous. For if the state or a profession can require

me to kill someone else - even if I am convinced that doing so is murder -

what can it not require?

Conclusion

How can we possibly have arrived at this point?

By first convincing people that contraception is a good thing, and that

physicians should be made to prescribe or refer for contraception.

By then convincing them that abortion is a good thing, and that

physicians should be made to perform or refer for abortion.

Finally, as Madame Justice Smith has demonstrated, by convincing people

that suicide, then assisted suicide, and then euthanasia are good things,

and that physicians should be made to provide or refer for them.

Convince people that X is a good thing - whatever X might be - and the

rest will follow - especially if X offers power, sex or relief from

suffering.

When laws governing abortion and contraception became less restrictive

almost fifty years ago, the kind of attacks now being made on physicians and

other health care workers who decline to provide or facilitate the services

was beyond imagining. No one would then have anticipated that the more

liberal society they thought they were building would generate the

vituperative intolerance now evident in Ontario.

So how can we know what the future holds for Catholic physicians and

others who share your beliefs if the Supreme Court legalizes assisted

suicide and euthanasia?

You might ask your three Ottawa colleagues.

And then you might read G.K. Chesterton's Ballad of the White Horse.

Closing

I again thank you for inviting me to speak tonight.

If my presentation has not been quite what you were expecting, I hope

that you will at least be able to thank Dr. Bright for referring a pleasant

61 year old gentleman to you for consultation.

Notes

1. Bill 52,

An Act respecting end-of-life

care.

(Hereinafter "ARELC.")

2.

Lee Carter, et al. v. Attorney General of

Canada, et al. Supreme Court of Canada, Case 35591

(Accessed 2014-11-24).

3. "The party must be of years of discretion,

and in his senses, else it is no crime. But this excuse ought not to be

strained to that length, to which our coroner’s juries are apt to carry

it, viz. that the very act of suicide is an evidence of insanity; as if

every man, who acts contrary to reason, had no reason at all: for the

same argument would prove every other criminal non compos, as well as

the self-murderer. The law very rationally judges that every melancholy

or hypochondriac fit does not deprive a man of the capacity of

discerning right from wrong; which is necessary, as was observed in a

former chapter, to form a legal excuse." Blackstone, William,

Commentaries on the Laws of England (12th ed), Vol. IV. London: A.

Strahan and W. Woodfall, 1795, p. 188-189.

4.

Carter v. Canada (Attorney General) 2012

BCSC 886. Supreme Court of British Columbia, 15 June, 2012. Vancouver,

British Columbia. (Hereinafter "Carter v. Canada") para. 339

(Accessed 2014-11-24) The qualifications "rationally and

morally"are implicit in the reasoning but not stated. The judge uses the

term "ethical," not "moral," and more frequently employs the former, but

she treats them as synonyms when addressing the question, "Does the law

attempt to uphold a conception of morality inconsistent with the

consensus in Canadian society?" (para. 340-358) Moreover, witnesses on

both sides do not typically distinguish between ethical and moral

issues. See, for example, Dr. Shoichet (plaintiffs) at para. 75, Prof.

Sumner (plaintiffs) at para. 237, Dr. Bereza (defendants) at para. 248,

Dr. Preston (plaintiffs) at para. 262. The judge defines ethics as "a

discipline consisting of rational inquiry into questions of right and

wrong" and frames the question accordingly: " whether it is right, or

wrong, to assist persons who request assistance in ending their lives

and, if it is right to do so, in what circumstances." Carter v. Canada,

para. 164. Most would see in this passage no way to distinguish between

ethics and moral philosophy.

5. Murphy S. "Legalizing therapeutic

homicide and assisted suicide: A tour of Carter v. Canada."-

VI.1-

Finding of "discrimination." Protection of Conscience Project.

6. Carter v. Canada, para. 16, 926,

1116, 1126, 1166, 1184-1185, 1187-1188, 1190, 1199, 1348, 1362

7. Carter v. Canada, para. 1172, 1348

8. For example, Carter v. Canada, para. 653,

815

9. Carter v. Canada, para. 1240

10. Carter v. Canada, para. 1243, 1283

11. CBC Radio,

Cross Country Checkup,

24 June, 2012.

(Accessed 2012-06-28).

12.

Section 4 of ARELC

states that eligible patients have a right to "end-of life-care," which

includes euthanasia and palliative care.

13. In the BCSC,

Amended Notice of Civil

Claim, Part 1, para. 64(c), Part 3, para. 5-7, 9-1; In the SCC on

appeal from the BCCA,

Factum of the Appellants,

para. 4, 123, 162-164, 182(e). (Accessed 2014-10-14)

14. Kirkey S.

"Doctor-assisted death

appropriate only after all other choices exhausted, CMA

president says." canada.com, 26 August, 2014

(Accessed 2014-10-06).

15. Beauchamp TL, Childress JF, Principles

of Biomedical Ethics (7th ed.) New York: Oxford University Press, 2013,

p. 176

16. Moore, O.

"Former Canadian army officer

accused of murder speaks out." Globe and Mail, 4 September, 2012.

(Accessed 2014-08-14).

17. Blackstone, W. Commentaries on the

Laws of England (12th ed.), Vol. 4. London: Strahan & Woodfall, 1795, p.

405. Citing 2 Hal. P.C. 412, 2 Hawk. P.C. 463

18.

ARELC, section 30.

19. Ann Furedi the chief executive of the

British Pregnancy Advisory Service, told New Zealanders that abortion is

required as a part of family planning programmes because contraception

is not always effective. She noted that abortion rates do not drop when

more effective means of contraception are available because women are no

longer willing to tolerate the consequences of contraceptive failure.

Abortion a necessary option: advocate. 18 October, 2010, TVNZ.

(Accessed 2014-02-15). Over twenty years ago, the U.S. Supreme Court

stated that "for two decades of economic and social developments, people

have organized intimate relationships and made choices that define their

views of themselves and their places in society, in reliance on the

availability of abortion in the event that contraception should fail.

The ability of women to participate equally in the economic and social

life of the Nation has been facilitated by their ability to control

their reproductive lives."

Planned Parenthood of Southeastern Pa. v.

Casey - 505 U.S. 833 (1992), p. 856

(Accessed

2014-02-15).

20. Cook Michael,

"First-world problems 2:

I’m really not into the whole 'turbo-euthanasia' thing." Bioedge, 27

June, 2013.

(Accessed 2014-07-15)

21. Carter v. Canada,

para. 311.

22. In the SCC on appeal from the BCCA,

Appellants' Response to Motions to Intervene,

20 June, 2014, para. 5(c)

23. Murphy S.

"Re: Joint intervention in

Carter v. Canada-Selections from oral submissions." Supreme Court of

Canada, 15 October, 2014. Joseph Arvay, Q.C. (Counsel for the

Appellants). Protection of Conscience Project.

24. Murphy S.

"Re: Joint

intervention in Carter v. Canada-Selections from oral submissions." Supreme

Court of Canada, 15 October, 2014. Jean-Yves Bernard (Counsel for the

Attorney General of Quebec) Protection of Conscience Project.

25. Consultations, Wednesday, 25 September

2013 - Vol. 43 no. 38: Quebec Association for the Right to Die with

Dignity (Hélène Bolduc, Dr. Marcel Boisvert, Dr. Georges L'Espérance),

T#107

26. In the SCC on appeal from the BCCA,

Factum of the Intervener, The Canadian Medical Association,

para. 3

27. In the SCC on appeal from the BCCA,

Factum of the Intervener, The Canadian Medical Association,

para. 28

28. In the SCC on appeal from the BCCA,

Factum of the Intervener, The Canadian Medical Association,

para. 27

29. In the SCC on appeal from the BCCA,

Factum of the Appellants

(13 May, 2014) para. 4, 123, 162-164 (Accessed 2014-10-14)

30. In the BCSC,

Amended Notice of Civil

Claim, Part 1, para. 55, 64(c); Part 3, para. 9-11, 18.

31. Carter v. Canada, para. 239-240.

Others have made the same claim: see Angell M., Lowenstein E.

"Letter

re: Redefining Physicians' Role in Assisted Dying." N Engl J Med

2013;

368:485-486 January 31, 2013 DOI: 10.1056/NEJMc1209798 (Accessed

2014-11-25)

32. Carter v. Canada, para. 120-130

33. Schuklenk U, van Delden J.J.M, Downie J,

McLean S, Upshur R, Weinstock D.

Report of the Royal Society of Canada

Expert Panel on End-of-Life Decision Making (November, 2011) p. 70

(Accessed 2014-02-23).

34. Carter v. Canada, para. 124

35. Consultations, Tuesday 17 September

2013 - Vol. 43 no. 34: Collège des médecins du Québec, (Dr. Charles

Bernard, Dr. Yves Robert, Dr. Michelle Marchand)

T#154

36. Collège des médecins du Québec,

Code of

Ethics of Physicians, para. 24

(Accessed

2013-06-23)

37.

ARELC, Section 50.

38. Murphy S. "Re: Joint intervention in

Carter v. Canada-Selections from oral submissions." Supreme Court of

Canada, 15 October, 2014.

Robert W. Staley (Counsel for the Catholic

Civil Rights League, Faith and Freedom Alliance, and Protection of

Conscience Project) Protection of Conscience Project.

39. In the SCC on appeal from the BCCA,

Factum of the Intervener, The Canadian Medical Association,

para. 27

40. In the SCC on appeal from the BCCA,

Factum of the Intervener, The Canadian Medical Association,

para. 27

41. Canadian Medical Association,

Reports to

the General Council. CMA 147th Annual General Meeting, August 17-20,

2014.

(Accessed 2014-11-20)

42. Canadian Medical Association,

Schedule

A: Legal Status of Physician Assisted Death (PAD) in Jurisdictions with

Legislation.

43. Vermont Statutes Title 18: Health,

Chapter 113:

An act relating to patient choice and control at end of

life. (Accessed 2014-11-20).

44. Belgium:

"At the request of the patient or the person taken in confidence, the

physician who refuses to perform euthanasia must communicate the

patient's medical record to the physician designated by the patient or

person taken in confidence."

Luxembourg: "A physician who

refuses to comply with a request for euthanasia or assisted suicide is

required, at the request of the patient or support person, to

communicate the patient's medical record to the doctor appointed by him

or by the support person."

Washington: "If a health

care provider is unable or unwilling to carry out a patient's request

under this chapter, and the patient transfers his or her care to a new

health care provider, the prior health care provider shall transfer,

upon request, a copy of the patient's relevant medical records to the

new health care provider."

Oregon: "If a health care

provider is unable or unwilling to carry out a patient's request under

ORS 127.800 to 127.897, and the patient transfers his or her care to a

new health care provider, the prior health care provider shall transfer,

upon request, a copy of the patient's relevant medical records to the

new health care provider."

45. Murphy S.

"Re: Joint intervention in

Carter v. Canada - Selections from oral submissions." Supreme Court of

Canada, 15 October, 2014. Harry Underwood (Counsel for the Canadian

Medical Association) Protection of Conscience Project.

46. Murphy S.

"NO MORE CHRISTIAN DOCTORS."

Protection of Conscience Project, March, 2014.

47. College of Physicians and Surgeons of

Ontario,

All Doctor Search

(Accessed

2014-07-29)

48. Payne E.

"Some Ottawa doctors refuse to

prescribe birth control pills." Ottawa Citizen, 30 January, 2014

(Accessed 2014-08-03)

49. Payne E.

"Some Ottawa doctors refuse to

prescribe birth control pills." Ottawa Citizen, 30 January, 2014

(Accessed 2014-08-03)

50.

Glauser W. "Ottawa clinic doctors’ refusal to offer contraception

shameful,

says embarrassed patient." Medical Post, 5 February, 2014

51. CBC Radio,

"Should doctors have the

right to say no to prescribing birth control?" Ontario Today, 25

February, 2014

(Accessed 2014-11-25)

52. Rodgers S. Downie J.

"Abortion: Ensuring

Access." CMAJ July 4, 2006 vol. 175 no. 1 doi: 10.1503/cmaj.060548

(Accessed 2014-02-23).

53. Schuklenk U, van Delden J.J.M, Downie

J, McLean S, Upshur R, Weinstock D.

Report of the Royal Society of Canada

Expert Panel on End-of-Life Decision Making (November, 2011) p.

101 (Accessed 2014-02-23)

54. Schuklenk U, van Delden J.J.M, Downie J,

McLean S, Upshur R, Weinstock D.

Report of the Royal Society of Canada

Expert Panel on End-of-Life Decision Making (November, 2011) p. 62

(Accessed 2014-02-23)

55.

Let their conscience be their guide?

Conscientious refusals in reproductive health care.

(Accessed 2014-11-21)

56. Let their conscience be their guide?

Conscientious refusals in reproductive health care.

(Accessed 2014-03-07)

57. Canadian Institutes of Health Research,

Let

Conscience Be Their Guide? Conscientious Refusals in Reproductive Health

Care- Project Information.

(Accessed 2014-11-25)