Submission to the Canadian Medical Association Re: 2018 Revision of the CMA Code of Ethics

Full Text

III. CMA on physician freedom of conscience

1988-2012: from abortion to euthanasia

III.1 In 1988, after the Supreme Court of

Canada struck down all legal restrictions on abortion, the CMA

revisited its policies on the procedure. The protection of

conscience provision in the Code of Ethics remained unchanged, and

the Association stressed that there should be no discrimination

against objecting physicians, "particularly for doctors training in

obstetrics and gynecology, and anesthesia."1

III.2 While this reaffirmed the CMA's

commitment to protect physician freedom of conscience, it does not

appear that the foundation for the commitment was explored or

developed over the next 25 years, even in the face of increasingly

strident claims that ultimately led to a recommendation that

objecting physicians should be forced to refer patients for

euthanasia.2

2012-2014: 'neutrality' and conscience

III.3 This issue suddenly came to the fore in

2012 when a ruling by a British Columbia Supreme Court judge struck

down the prohibition of physician assisted suicide and euthanasia.3

When the CMA Annual General Council convened in August, 2013, an

appeal of the Carter decision was in progress, and a euthanasia bill

had been introduced in the Quebec legislature. Council proceedings

reflected "deep divisions within the medical community."4 The Council

did, however, resolve to support "the right of any physician to

exercise conscientious objection when faced with a request for

medical aid in dying." (DM 5-22)5

III.4 CMA officials spent much of 2014 studying

euthanasia and assisted suicide, and in August presented the General

Council with a resolution affirming CMA support for both physicians

unwilling to participate in the procedures, and those willing to do

so, should they be legalized.6 This was explained by CMA officials as

a commitment to neutrality and support for physician freedom of

conscience.7,

8, 9

III.5 However, when the executive revised the

policy in December, it formally approved physician assisted suicide

and euthanasia as "end of life care" and promised to support patient

access to "the full spectrum" of such care, subject only to the law.

The policy did not exclude minors, the incompetent or the mentally

ill, nor did it indicate that the procedures should be provided only

to the terminally ill or those with uncontrollable pain. It referred

directly only persons suffering from "incurable diseases."10 The

Directors thus formally committed the Association to support

euthanasia and assisted suicide not only for competent adults, but

for any patient group and for any reason approved by the courts or

legislatures.

III.6 From a protection of conscience

perspective, the first practical problem with this was that actual

support for euthanasia and assisted suicide within the medical

profession - to the extent that it had been evaluated at all - was

highly volatile. Roughly contemporaneous optimistic estimates

suggested that 6% to 29% of physicians were willing to provide the

procedures, depending upon the condition of the patient; 63% to 78%

would refuse, again dependent upon the condition of the patient. Of

physicians willing to consider providing the services, the number

dropped by almost 50% in the case of non-terminal illness, and by

almost 80% in the case of purely psychological suffering (i.e., in

the absence of pain).11 The Association's unconditional support for

euthanasia and assisted suicide potentially exposed large number of

physicians to demands that could generate serious conflicts of

conscience.

III.7 The second problem was that the policy

was not neutral.12 By classifying euthanasia and assisted suicide as

"end of life care," the CMA executive effectively made participation

in euthanasia and assisted suicide normative for the medical

profession. Once the Supreme Court of Canada ordered legalization of

the procedures,13 the refusal to provide assisted suicide and

euthanasia in the circumstances set out in Carter became an

exception to professional obligations that had to be justified or

excused. This is why, since Carter, public discourse has largely

centred on whether or under what circumstances physicians and

institutions should be allowed to refuse to provide or participate

in homicide and suicide.

III.8 Certainly, the new policy also stated

that the CMA supported the right of physicians to "follow their

conscience" when deciding whether or not to provide euthanasia, and

that physicians "should not be compelled to participate," a broader

term that could encompass referral. However, it characterized the

protection of conscience provision in the Code of Ethics (2004

paragraph 12) as defending only "physician autonomy," not physician moral

agency and personal integrity. In

addition, it added a qualifying statement: "However, there should be

no undue delay in the provision of end of life care." This could be

(and later was) understood to justify limiting freedom of conscience

for objecting physicians in order to ensure patient access to the

services.

2015: the Carter maelstrom

III.9 Thus, when the Supreme Court ruled in

Carter, the CMA was ready to proceed with implementing euthanasia

and assisted suicide, but it was quite unprepared mount a cogent,

articulate and persuasive defence of physician freedom of

conscience. This disadvantage was compounded when the federal

government did virtually nothing for five months following the

ruling, then called (and lost) an election, and left the CMA other

stakeholders scrambling to develop policies responsive to the Carter

ruling without any direction as to what changes would be made to the

criminal law.

III.10 The result was a policy and regulatory

maelstrom that lasted several months. During this time, CMA

officials, struggling to develop practice standards and guidelines

in response to Carter, were also caught between activists demanding

that physicians be compelled to refer for the procedures, and

physicians and physician groups, galvanized by the Carter ruling,

adamantly opposed to providing or facilitating euthanasia or

assisted suicide. Under the circumstances, it is not surprising that

there was some waffling by CMA officials on the issue of referral.

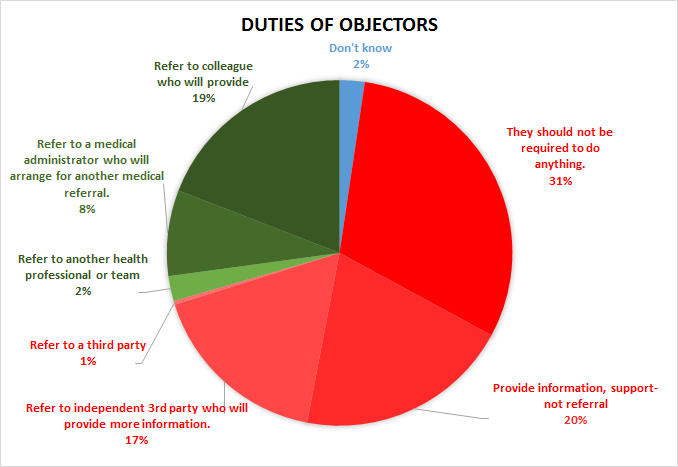

III.11 By the time the Annual General Council

convened in August, 2015, only about 19% of CMA members believed

that physicians should be required to refer patients to someone who

would provide euthanasia or assisted suicide. Almost 70% were

opposed to the idea. About 31% thought objecting physicians should

not be require to do anything, but about 27% believed that they

should provide information and support, or refer to a third party

who

could provide information.

Source: Murphy S. A

"uniquely Canadian approach" to freedom of conscience in health care: Provincial-Territorial Experts recommend coercion to ensure delivery of euthanasia and assisted suicide. App.

D2.2.3. Protection of Conscience Project (2016).

Source: Murphy S. A

"uniquely Canadian approach" to freedom of conscience in health care: Provincial-Territorial Experts recommend coercion to ensure delivery of euthanasia and assisted suicide. App.

D2.2.3. Protection of Conscience Project (2016).

III.12 The Council ultimately approved a resolution

later adopted by the CMA Board of Directors. It stated that physicians were

not obliged to fulfill requests for or participate in euthanasia or assisted

suicide, and should not be discriminated against for refusing to do so. It

required objecting physicians to provide patients with complete information

on "all options," and advise them "how they can access any separate central

information, counseling, and referral service."14

III.13 This was a development of the basic

framework provided by the Code of Ethics. It was, however, a largely

pragmatic response guided by a general notion of "striking a

balance" between patient and physician autonomy or rights. It was

specific to euthanasia and assisted suicide, and it was unsupported

by principled ethical or philosophical rationale. It is unlikely

that more than this could have been achieved in the circumstances.

2016: The CMA and "effective referral"

III.14 The first CMA statement addressing the

subject of physician freedom of conscience at a foundational level

was a 2016 submission to the College of Physicians and Surgeons of

Ontario in response to its demand that objecting physicians

facilitate euthanasia and assisted suicide by an "effective

referral."15 Important elements of this statement were incorporated

into the new CMA Medical Assistance in Dying policy and are evident

in the 2018 revised draft of the CMA Code of Ethics.

III.15 The first and most important element is

the recognition of physicians as moral agents.

It is in fact in a

patient's best interests and in the public interest for physicians

to act as moral agents, and not as technicians or service providers

devoid of moral judgement. At a time when some feel that we are

seeing increasingly problematic behaviours, and what some view as a

crisis in professionalism, medical regulators ought to be

articulating obligations that encourage moral agency, instead of

imposing a duty that is essentially punitive to those for whom it is

intended and renders an impoverished understanding of conscience.

III.16 The statement does not neglect the

interests of patients seeking access to euthanasia and assisted

suicide, noting that the CMA wishes to protect physician freedom of

conscience "without in any way impeding or delaying patient access."

However, it insists that this can be accomplished by adopting a

two-pronged strategy: by asking physicians to fulfil "a duty that is

widely morally acceptable," yet allows them " to act as moral

agents," and by requiring the community to accept its responsibility

to ensure access, "rather than placing the burden of finding

services solely on individual physicians."

III.17 The third significant point is recognition that the

central concern of objecting physicians is their individual moral

responsibility to avoid complicity in perceived wrongdoing. This is

sometimes misconstrued or misrepresented as a desire to control the

conduct of their patients, and it is too often passed over because

it can be a painful reminder of the essential point of disagreement

between objecting physicians and non-objecting colleagues.

III.18 Fourth, the statement recognizes that

the exercise of freedom of conscience is a fundamental freedom for

everyone, not just for those whose moral judgement conforms to a

dominant viewpoint, or to one's own. This is implied in its

discussion of effective referral. Some physicians who refuse to

provide assisted suicide or euthanasia have no objection to

referring a patient to a colleague willing to provide the service.

Others find referral "categorically morally unacceptable" because

they believe that referral makes them complicit in grave wrongdoing.

The statement characterizes a demand for "effective referral" as

illicit discrimination, not a solution, because it "respects the

conscience of some, but not others."

It is the CMA's strongly

held position that there is no legitimate justification to respect

one notion of conscience . . . the CMA [seeks] to articulate a duty

that achieves an ethical balance between conscientious objection and

patient access in a way that respects differences of conscience. It

is the CMA's position that the only way to authentically respect

conscience is to respect differences of conscience.

III.19 Finally, citing the Supreme Court of

Canada, the statement also emphasizes the fiduciary nature of the

patient-physician relationship: the physician's obligation "to

protect and further their patients' best interests." However, it

adds that physicians' fiduciary obligations do not "in any way"

entail an obligation to violate their own moral integrity.

III.20 The Project has strongly supported this

position for years. However, something more must be added to this.

The dominant view is that "the interests" or "best

interests" of patients are determined by the patients themselves -

not by physicians - even if physicians assist them in deciding what

those interests are. Once patients have identified their interests,

the argument goes, physicians have a fiduciary duty to serve those

interests, by, for example, referring a patient for a desired

procedure. This is erroneous.

III.21 Granted that patients are entitled

to determine what they believe to be in their best interests,

physicians who disagree have no obligation to serve those interests.

As a matter of law, a fiduciary is not a servant.16 Fiduciaries have a

duty not to act under dictation, even the dictation of a

beneficiary,17 and must exercise their own judgement.18 The law does not

allow beneficiaries (patients) to turn fiduciaries (physicians) into

"puppets."19 These are important legal principles that apply to all

aspects of clinical and professional judgement, not just to the

exercise of freedom of conscience.

Conclusion

III.22 The CMA’s support for physician freedom

of conscience has been expressed by resolutions at successive

General Councils. In addition, available statistics indicate that

the great majority of CMA members have been opposed to compelling

objecting physicians to refer for morally contested services, but

seem to agree that there is an obligation to provide information and

to help patients contact other physicians or health care providers.

III.23 Like the 2018 Revision, the CMA's first

statement addressing physician freedom of conscience at a

foundational level emphasizes physician moral agency and integrity.

However, it strongly denounces the imposition of effective referral,

describing it as illicitly discriminatory. This ought to preclude

acceptance of the proposal for referral and physician-initiated

transfer of care in the current text of 2018 Revision C3.

Notes

1. Canadian Medical Association. Policy:

Induced abortion. [Internet] 1988 Dec 15 [cited 2018 Mar 15].

2. Schuklenk U, van Delden JJM, Downie J,

McLean S, Upshur R, Weinstock D.

Report of the Royal Society of Canada Expert Panel on End-of-Life

Decision Making. [Internet] Royal Society of Canada. 2011 Nov.

117 p. [cited 2018 Mar 25] at 69, 101.

3.

Carter v. Canada (Attorney General) 2012 BCSC 886

[Internet] [cited 2018 Mar 15].

4. Eggertson L.

CMA delegates

defer call for national discussion of medically assisted death. CMAJ

[Internet] 2013 Sep 17 [cited 2018 Mar 15];185(13): E623-624.

5. Canadian Medical Association.

Resolutions Adopted,146th Annual Meeting of the Canadian Medical

Association (Calgary, AB) [Internet]. 2013 Aug 19-21 [cited 2022 Oct 8].

6. Canadian Medical Association. 147th

General Council Delegates' Motions [Internet].

End-of-Life Care: Motion DM 5-6 [cited 2022 Oct 8].

7. Kirkey S. Canadian doctors seek freedom to choose whether to offer medical aid in dying. Montreal Gazette [Internet] 2014 Aug 20 [cited 2022 Oct08].

8. Swan M.

Medical association vows to protect conscience rights. The

Catholic Register [Internet]. 2014 Aug 27 [cited 2018 Mar 15].

9. McFadden J.

Yk docs

bring motions on doctor-assisted death: Canadian law on euthanasia could

be overturned by next month. Northern News Services [Internet]. 2014

Sep 8 [cited 2018 Mar 29].

10. Canadian Medical Association. Policy:

Euthanasia and Assisted Death [Internet]. Update 2014 [cited 2022 Oct 08].

11. Murphy S. A "uniquely Canadian approach" to

freedom of conscience: Provincial-Territorial Experts recommend coercion

to ensure delivery of euthanasia and assisted suicide." Appendix "D":

Canadian Medical Association on euthanasia and assisted suicide.

D2.1:

Surveys on support for euthanasia/assisted suicide.

12. Contrast the position of the CMA with

that of the Royal New Zealand College of General

Practitioners, which explicitly declined to endorse euthanasia or

assisted suicide, while recognizing that individual practitioners might

participate if they wished to do so. The Royal New Zealand College

of General Practitioners.

Submission to the Justice Committee re: End of Life Choice Bill

[Internet]. 2018 Mar 6 [cited 2022 Oct 08].

13.

Carter v. Canada (Attorney General), 2015 SCC 5 [Internet]

[cited 2018 Mar 14].

14. Canadian Medical Association.

Principles-based Recommendations for a Canadian Approach to Assisted

Dying. In: CMA Submission to the Federal External Panel on Options

for a Legislative Response to Carter vs. Canada (Federal External Panel)

[Internet]. 2015 Oct 19

[cited 2022 Oct 08]. A2-1 to A2-6 at A2-1,

Foundational Principle 2.

15. Canadian Medical Association.

Submission to the College of Physicians and Surgeons of Ontario:

Consultation on CPSO Interim Guidance on Physician-Assisted Death.

[Internet] 2016 Jan 13.

16.

Canadian Aero Service Ltd. v.

O'Malley, [1974] SCR 592, 1973 CanLII 23 (SCC)

[Internet][cited 2018 Mar 29] ("their

positions . . .charged them with initiatives and with

responsibilities far removed from the obedient role of servants. It

follows that O'Malley and Zarzycki stood in a fiduciary relationship

to Canaero . . ." at 606).

17. United Kingdom, Law Commission, Report

No. 350.

Fiduciary Duties of Investment Intermediaries. Williams Lea

Group for HM Stationery Office. [Internet] 2014 [cited 2022 Oct 08] at para 3.53, note 107, citing

Selby v Bowie (1863) 8 LT 372; Re Brockbank [1948] Ch 206.

18. Ibid, notes 109–110, citing

Thomas G. Thomas on Powers. 2nd ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press;

2012, at para 10.60; Finn P. Fiduciary Obligations. 1st ed. Sydney: Law

Book Co; 1977, at para 44; Mowbray J et al. Lewin on Trusts. 18th ed.

London: Sweet & Maxwell; 2007, at para 29-89.

19. Ibid, para 3.51 note 105,

quoting Finn P. supra note 18 at para 42.

Prev | Next