A "uniquely Canadian approach" to freedom of conscience

Provincial-Territorial Experts recommend coercion to

ensure delivery of euthanasia and assisted suicide

Appendix "D"

Canadian Medical Association on euthanasia and assisted suicide

Full Text

D1. CMA policy: Euthanasia and Assisted Death

(2014)

D1.1 The policy of the Canadian Medical Association (CMA)

on euthanasia and physician assisted suicide (which the CMA calls "assisted

death") does not exclude minors, the

incompetent or the mentally ill, and the policy is not meant to apply only

to the terminally ill or those with uncontrollable pain. It refers directly

only to "patients" and "the suffering of persons with incurable diseases."

The policy, which predates the Carter ruling, classifies euthanasia

and assisted suicide as "end of life care." Under this rubric, the CMA

supports patient access to euthanasia and assisted suicide for any patient

group for any reason and under any circumstances approved by the courts or

legislatures.1

D1.2 By formally approving physician assisted suicide and

euthanasia under circumstances defined by law, the Association has taken the

position that, in those circumstances, physicians have a professional

obligation to kill patients or to help them kill themselves.2 By describing

this as "end of life care," the CMA has made homicide and suicide normative

for the medical profession. It is the refusal to kill patients or assist in

suicide in the circumstances set out in Carter that must be justified or

excused as an exception to professional obligations.

D1.3 Thus, the CMA is prepared to support the exercise of

freedom of conscience and religion by objecting physicians only to the

extent that this does not compromise patient access to euthanasia and

assisted suicide. However, it sets no limits on what non-objecting

physicians might agree to do beyond what might be set by law.

Notwithstanding claims that the Association supports both physicians willing

to provide euthanasia and assisted suicide and those who do not, the

weight and influence of the entire Association has been set against

physicians who believe that it is wrong to kill patients or help them to

kill themselves, or, at least, that physicians should not do so.

D1.4 The formal support of the CMA for

a euthanasia/assisted suicide regime even broader than that proposed in

Carter appears to be in tension with the opinions of many CMA members,

not just objecting physicians. Unlike the Experts, Canadian physicians

are anything but unanimous in their

opinions about euthanasia and physician assisted suicide, and support for

the Carter decision among them is hardly unqualified. This has been

obscured by a habit of presenting the most optimistic view of physician support for

the procedures.

D1.5 Both the habitually optimistic approach and the

volatile nature of the opinions of physicians were evident in the analysis

of CMA surveys offered to delegates at the Annual General Council

(AGC) in August, 2015.

D2. CMA Annual General Council, 2015

D2.1 Surveys on support for

euthanasia/assisted suicide

D2.1.1 A report prepared by CMA officials stated that

"recent polls show that CMA members are evenly divided on the issue of

legalizing assisted dying, and a significant minority of respondents to

these polls said they will participate in offering this service to their

patients."3 The report referred to an

on-line dialogue in which 595 CMA members (less than 1% of the CMA's 80,000

members) "registered to participate."4

It did not acknowledge that only about 150 physicians contributed comments

to the dialogue.

D2.1.2 The details were provided in a presentation by Dr. Jeff Blackmer

at the AGC. Most of his presentation drew from two on-line surveys of about

1.75% and .465% of the CMA membership.

D2.1.3 Using slides, he produced what he called "the key

on-line survey results" of a poll taken after the Carter ruling.

The 2015 survey to which he referred appears to be the on-line survey

consultation survey completed by 1,407 physicians.5 The question asked was,

"Following the Supreme Court of Canada decision regarding medical aid in

dying, would you consider providing medical aid in dying if it was requested

by a patient?"6

D2.1.4 The survey question did not distinguish between

assisted suicide or euthanasia, so we do not know if the respondents

believed that they were answering a question about euthanasia, assisted

suicide or both.

D2.1.5 From the very first, reports about the Carter

decision in the major media constantly and almost uniformly described the

decision as legalizing physician assisted suicide, with no reference to

euthanasia. Dr. Blackmer himself, two weeks after the ruling, claimed that

he was uncertain whether the Court legalized only physician assisted

suicide, or euthanasia as well.7

D2.1.6 Since significantly fewer physicians are willing to

provide euthanasia than assisted suicide,8 the failure to distinguish between

them introduces some uncertainty into the interpretation of the results.

D2.1.7 Note that the survey asked only if physicians would

"consider" providing the procedures, not if they would actually do so.

D2.1.8 29% of those surveyed stated that they would

"consider" it. "That might seem to be a very small percentage," Dr. Blackmer

said, "but when you think of it in terms of absolute numbers, we're talking

tens of thousands of Canadian physicians that are now saying, 'I will

participate.'"9

D2.1.9 Here we see the habitual optimism noted above (D1.4).

In fact, the respondents stated that they would "consider" participating,

not that they would participate. Further, while "tens of thousands" was

arithmetically accurate (29% of 80,000 = 23,200 physicians = 2 x 10,000), the rhetorical slant was toward an optimistic evaluation of the

returns.

D2.1.10 Continuing to 'unpack' the survey results, Dr.

Blackmer told delegates that, of the physicians willing to consider

providing either euthanasia or assisted suicide, "only 20% said yes" with

respect to "someone whose suffering was purely psychological." The actual

number noted in the chart on the slide was 19%, not 20%. He acknowledged

that the response from this statistical subset represented about 6% of the

total number of respondents.10

D2.1.11 "And when we asked, 'Would you provide medical aid

in dying to someone who is not suffering from a terminal illness,' he said,

'43% said yes.'"11

D2.1.12 Dr. Blackmer did not draw attention to the fact that

this appears to represent only about 14% of the total number of respondents.

His slides illustrated the responses proportionate to the subset, not to the

total number of respondents, so the graphic images reflected proportionately

greater support for euthanasia and assisted suicide among respondents (19%

vs. 6%; 43% vs. 14%).

D2.1.13 The slides in the video below draw on the same data

used by Dr. Blackmer in the preceding slides, but graphically represent the

increasingly adverse responses to the conditions specified by the survey

questions.

D2.1.14 An alternative and arguably more useful rendering of

the 2015 survey results is possible.12

● The number of physicians willing to provide euthanasia or assisted suicide

appears to range from 6% to 29%, depending upon the condition of the

patient, and excluding consideration of safeguards.

● The number of physicians unwilling to provide euthanasia or assisted

suicide ranges from 63% to 78%, again depending upon the condition of the

patient, and excluding consideration of safeguards.

● Of physicians willing to consider providing euthanasia or assisted

suicide, the number willing to provide the procedures for non-terminal

illness drops by almost 50% , and drops by almost 80% in the case of purely

psychological suffering (i.e., in the absence of pain), excluding

consideration of safeguards.

D2.1.15 Dr. Blackmer presented a much more optimistic view.

He showed delegates a slide with pie

charts side by side for the purpose of comparing surveys done in 2014,

before the Carter ruling, and in 2015, after it. Delegates

had 24 seconds to take in the following charts and his commentary before he

moved to the next slide.

Blackmer:

So this is before the court decision and after the court decision. And you

can see that the number of participants who said that they were very likely

or likely to participate in assisted dying has actually gone up, from 24% to

29% since the Supreme Court decision.13

D2.1.16 He did not point out that the number of physicians

unwilling to consider providing the service also went up by 5% after the Carter ruling,

from 58% to 63%.

D2.1.17 Again, the survey question asked physicians if they

would consider providing the services, but Dr. Blackmer presented

the responses as indicative of the number of physicians actually willing to

do so.

D2.1.18 Apparently to reinforce the message he wanted to get

across, Dr. Blackmer introduced slides to present data from a survey of

family physicians concerning the Carter decision.14 He cautioned

delegates that "the numbers are a little smaller."15 A "little smaller" seems

to minimize the difference: 372 members compared to 1,407.

D2.1.19 In any case, Dr. Blackmer told delegates that "59% of

members actually said, 'Yes, I agree with that,' so over half of physicians

agreed with the Supreme Court decision."16

Blackmer:

And when they asked, "Would you help a competent, consenting patient end his

or her life," a total of 66% actually said "yes," although most of those -

54% - said, "Yes, but only if appropriate and rigorous checks and balances

are in place.17

D2.1.20 Assuming both slides drew from 372 responses, more

physicians agreed with the Carter decision than were willing to

provide assisted suicide and euthanasia. 27% disagreed with the decision,

but 33% said they would "never" help patients end their lives.

D2.1.21 On the other hand, willingness to

provide euthanasia or assisted suicide was conditional. As Dr. Blackmer

noted, 66% were willing to do so, but the number dropped to 12% in the

absence of "appropriate rigorous checks and balances."

D2.1.22 Most important, Dr. Blackmer left out one critical

word. The actual question (as stated on the slide) was, "Would you help a

competent, consenting DYING patient end his or her life." (Emphasis added)

D2.1.23 The CMA's larger

survey demonstrated that support for euthanasia and assisted suicide among

physicians willing to provide it can drop by almost 50% if the patient is

not terminally ill (D2.1.12-D2.13).

The slide was displayed for only about 15 seconds, so it is doubtful that

many delegates had a chance to reflect on the fact that the survey asked

only about dying patients.

D2.1.24 An alternative and more cautious account of the

College of Family Physicians survey results is possible.

-

Since the Carter decision legalized euthanasia and assisted

suicide for patients who are neither dying nor terminally ill, the value of

the survey in the post-Carter medico-legal landscape is doubtful.

-

In the absence of "appropriate rigorous checks and balances," the number

of family physicians willing to provide euthanasia or assisted suicide drops to only 12% of the total number of respondents.

D2.1.25 Taking time to look at the numbers just as they were

presented,

they did not support the claim that

physicians were "evenly divided" in their opinions about euthanasia and

assisted suicide. The returns indicated that the great

majority of physicians were opposed to both.

Moreover, support for the procedures among favourably disposed physicians

was

highly volatile, depending heavily upon the diagnosis, the condition of the

patient and the rigour of the regulatory regime.

D2.1.26 This was reflected in the Globe and Mail

headline: "Less than a third of doctors willing to aid in assisted dying."18

The National Post response was similar: "Majority of doctors

opposed to participating in assisted death of patients."19 The Canadian

Medical Association Journal acknowledged that "Many doctors won't

provide assisted dying."20

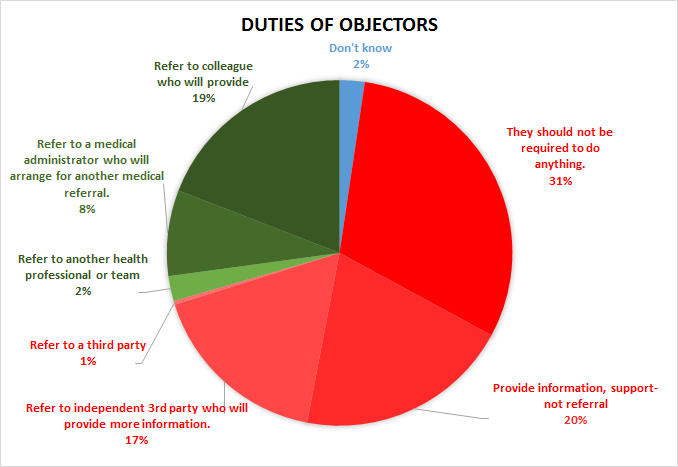

D2.2 Physician freedom of conscience

D2.2.1 Dr. Blackmer introduced what he described as "the

very complex and difficult issue of conscientious objection" with the

results of the on-line survey.21 With respect to the question of what a

physician who refuses to provide euthanasia or assisted suicide should be

required do, "the most popular response" (29%) was, "They should not be

required to do anything."

D2.2.2 25% of the responses were categorized as "other"; this was

unexplained at the General Council.22 The

CMA kindly provided the Project with the summary of the returns

under the category "Other," broken down as follows:

Q4_Other (Please specify). 341 relevant comments, grouped by theme:

|

Provide information and support, but not

referral

|

283 comments

83.0%

|

|

Refer to another health professional or team of

professionals

|

33 comments

9.7%

|

|

Not required to do anything

|

20 comments

5.9%

-

2 comments from respondents who WOULD

consider providing medical aid in dying if it was requested

by a patient

-

18 comments from respondents who would NOT

consider providing medical aid in dying if it was requested

by a patient

|

|

Refer to a third party

|

5 comments

1.5%

|

D2.2.3 When joined to the information that was disclosed at

the Annual General Council (approximated in the Project chart below), it

appears that the great majority of respondents (about 68%) clearly believed

that objecting physicians should not

be required to refer patients for anything other than information.

Protection of Conscience Project Chart

D2.2.4 "Effective referral" was favoured by 19% of

respondents, 10% less than the number of physicians who identified

themselves as willing to consider providing euthanasia or assisted suicide

(D2.1.3).

D2.2.5 Returning to the subject later in his presentation,

Dr. Blackmer noted that "the vast majority expressed the view that physician

conscience rights must be integrally protected." He reminded delegates of

the resolution passed at the 2013 Annual ' Council "saying that no

physician should be forced to participate in an assisted dying against their

moral conscience," adding that "the Supreme Court noted that in their

ruling." However, he cautioned that "there was disagreement about was this

means."23 Finally, he stated that there was "broad agreement" that physician

freedom of conscience "must be protected in a way that balances patients'

ability to access assisted dying."24

D2.2.6 Here he referred to four options for physicians who

refuse to provide euthanasia or assisted suicide, somewhat different from

those presented in the on-line consultation:25

1. Duty to refer directly to a non-objecting physician

2. Duty to refer to an independent third party.

3. Duty to provide complete information on all options and advise on how to

access directly a separate central information, counselling and referral

service.

4. Patient self-referral to a separate central information, counselling and

referral service.

D2.2.7 In listing the "pros" and "cons" of each, he

acknowledged that the third "may be the most widely morally acceptable

option," but warned that it presupposed the existence of a separate

counselling service - "a fairly large presupposition at this point in time."26

D2.2.8 The third option was a summary of what had been

proposed to the CMA by the Christian Medical Dental Society, the Federation

of Catholic Physicians Societies and Canadian Physicians for Life. The

groups urged delegates to accept it for the following reasons:

Options '1' and '2' require the objecting physician to refer. Many

physicians will have moral convictions that assisted death is never in the

best interests of the patient, while others may object to assisted death

because of the particular circumstances of the patient. A referral is

essentially a recommendation for the procedure, and facilitates its

delivery. A requirement to refer means that physicians will be forced to act

against their consciences.

Option '4' allows the patient to directly access assisted death, but does

not necessarily provide an opportunity for counselling by a physician who

has a longer term relationship with the patient.

Option '3' allows the discussion of all options to occur with the patient

and the physician who knows them. If, after considering all of the options,

the patient still wants assisted death, the patient may access that

directly. This option ensures that all reasonable alternatives are

considered. It respects the autonomy of the patient to access all legal

services while at the same time protecting physicians' conscience rights.27

D2.2.9 After a lengthy discussion, the third option was

approved in a straw poll, supported by about 75% of the delegates, who

agreed that "physicians should provide information to patients on all

end-of-life options available to them but should not be obliged to refer."18

D2.2.10 This account of the outcome is consistent with the

fact that only the first two options included a "duty to refer," while the

third did not. A further point, which would not have been apparent to

the delegates at the time, was that the outcome reflected the (undisclosed)

fact that 69% of survey respondents had indicated that they were opposed to

a requirement to refer to someone who would provide euthanasia or assisted

suicide (D2.2.3).

D2.2.11 The day after the delegates approved the third option

(a duty to provide information), Dr. Ken Burns and Dr. Shawn Whatley

proposed another resolution specific to referral:

The Canadian Medical Association policy on physician-assisted death will

reflect that physicians with consciencious [sic] objections should not be

obligated to refer for medical aid in dying. [Motion DM 5-60]28

D2.2.12 The rationale offered in support of the motion

repeated the kind of arguments made the day before:

CMA has indicated (survey and draft document) that referral is an acceptable

method to deal with a physician's conscience conflict. This not true for

many physicians. A forced referral (even through another party) for a

procedure they believe is wrong is not protecting conscience. CMA has

opposed the College of Physicians and Surgeons of Ontario's new policy but

appears to be backing down in its position. ' Council needs to decide

if it is going to protect even a minority of members' legal rights.

A very large number of CMA membership see any form of forced referral

against their conscience.They expect their organization to support their

fundamental rights.29

D2.2.13 However, after significant opposition from a number

of delegates, the motion was defeated, 79% of them voting against it.30

D2.2.14 The most likely explanation for this is the terminological problem that plagues discussion about "referral." It has a

technical meaning: a letter written by a physician to another physician

requesting treatment examination. It also has a popular meaning: some kind

of informal direction to a patient about where to obtain or how to find a

service or treatment. It is likely that many of the delegates who had, the

day before, approved the third option, considered it to be a form of

referral in the second sense. In that case, they likely rejected the

resolution because it appeared to them to contradict what they had approved

the previous day.

D2.2.15 Unfortunately, the rejection of the second motion

created the impression in some quarters that the CMA was opposed to

physician freedom of conscience. For example, Alex Schadenburg of the

Euthanasia Prevention Coalition reported that the CMA "voted to reject a

motion to protect the conscience rights of physicians who refuse to refer

patients to die by euthanasia."31 The

Western Catholic Reporter published a

story quoting Mr. Schadenburg under the headline, "Doctors to lose

conscience rights under CMA decision."32

D2.2.16 At their October, 2015 meeting, the CMA Board of

Directors approved Principles-based Recommendations for a Canadian Approach

to Assisted Dying as amended in consequence of the discussion at the Annual

' Council.33 The section on conscientious objection stated:

Physicians are not obligated to fulfill requests for assisted dying. There

should be no discrimination against a physician who chooses not to

participate in assisted dying. In order to reconcile physicians'

conscientious objection with a patient's request for access to assisted

dying, physicians are expected to provide the patient with complete

information on all options available to them, including assisted dying, and

advise the patient on how they can access any separate central information,

counseling, and referral service.34

D2.2.17 This was included the the CMA presentation on 20

October, 2015 to the panel

appointed by the federal government to report on the implementation of the

Carter ruling. The CMA offered the

following comments:

As the Federal External Panel is aware, the Carter decision emphasizes that

any regulatory or legislative response must seek to reconcile the Charter

rights of patients (wanting to access assisted dying) and physicians (who

choose not to participate in assisted dying on grounds of conscientious

objection). The notion of conscientious objection is not monolithic. While

some conceptions of conscience encompass referral, others view referral as

being connected to, or as akin to participating in, a morally objectionable

act.

It is the CMA's position that an effective reconciliation is one that

respects, and takes account of, differences in conscience, while

facilitating access on the principle of equity. To this end, the CMA's

membership strongly endorses the recommendation on conscientious objection

as set out in section 5.2 of the CMA's enclosed Principles-based

Recommendations for a Canadian Approach to Assisted Dying.35

D2.2.18 The section in the document concerning

conscientious objection was later modified by the Board of Directors.

The revision did not change the original section (in blue font below),

but added further details.

Physicians are not obligated to fulfill requests for assisted dying. This

means that physicians who choose not to provide or participate in assisted

dying are not required to provide it or participate in it or to refer the

patient to a physician or a medical administrator who will provide assisted

dying to the patient. There should be no discrimination against a physician

who chooses not to provide or participate in assisted dying.

Physicians are obligated to respond to a patient’s request for assistance

in dying. There are two equally legitimate considerations: the protection of

physicians’ freedom of conscience (or moral integrity) in a way that

respects differences of conscience and the assurance of effective patient

access to a medical service. In order to reconcile physicians’ conscientious

objection with a patient’s request for access to assisted dying, physicians

are expected to provide the patient with complete information on all options

available, including assisted dying, and advise the patient on how they can

access any separate central information, counseling, and referral service.

Physicians are expected to make available relevant medical records (i.e.,

diagnosis, pathology, treatment and consults) to the attending physician

when authorized by the patient to do so; or, if the patient requests a

transfer of care to another physician, physicians are expected to transfer

the patient’s chart to the new physician when authorized by the patient to

do so.

Physicians are expected to act in good faith, not discriminate

against a patient requesting assistance in dying, and not impede or block

access to a request for assistance in dying.36

D3. CMA rejects "effective referral"

D3.1 The Canadian Medical Association has continually

grappled with the issue of referral for morally contested procedures since

at least 1970, when the CMA Board of Directors decided that it would be

ethical for a physician to refer a patient to another physician for

consideration of an abortion, but not to an "abortion counselling agency."37

The difficult compromise eventually arrived at required objecting physicians

to disclose personal moral convictions that might prevent them from

recommending a procedure to patients, but did not require the physician to

refer the patient or otherwise facilitate the morally contested procedure.38

D3.2 It appears that the compromise was primarily a

pragmatic response to controversy. At any rate, the CMA did not offer

a principled ethical or philosophical rationale to support it, beyond

general references to the need to "strike a balance" between patient and

physician autonomy or rights. In 2014/2015, when the College of

Physicians and Surgeons of Ontario (CPSO) developed a policy requiring

objecting physicians to make an "effective referral," the CMA was notably

absent from the public controversy surrounding it.

An effective

referral means a referral made in good faith, to a non-objecting, available,

and accessible physician, other health-care professional, or agency. The

referral must be made in a timely manner to allow patients to access care.

Patients must not be exposed to adverse clinical outcomes due to a delayed

referral.39

D3.3 However, a crisis of sorts seems to have been

generated by the Carter ruling, as physicians awakened to its

implications for freedom of conscience and religion and even for the

legitimate diversity of clinical judgement. Within this context, the

perennially controversial issue of referral became more urgent, with

literally life or death consequences attached to it. Perhaps as a

result, the CMA has now issued a statement that articulates the basis for

its rejection of "effective referral," this time in response to CPSO plans

to impose "effective referral" for euthanasia and assisted suicide.40

Notes:

1. Canadian Medical Association Policy:

Euthanasia and Assisted Death (Update 2014)

(Accessed 2015-06-26).

2. Blackmer J, Francescutti LH, "Canadian Medical

Association Perspectives on End-of-Life in Canada." HealthcarePapers, 14(1)

April 2014: 17-20.doi:10.12927/hcpap.2014.23966

3. Canadian Medical

Association,

A Canadian Approach to Assisted Dying: A

CMA Member Dialogue Summary Report. (August, 2015)

p. 2 (Accessed 2015-10-23). (Hereinafter, "Summary Report").

4. Summary Report, p.2.

5.

Canadian Medical Association Annual General Council 2015,

Education

session 2: Setting the context for a principles-based approach to

assisted dying in Canada. Webcast- 13:40-13:45. (Hereinafter

"Ed2-webcast")(Accessed 2015-12-29)

6. Ed2-webcast - 15:00-15:22

7. Kirkey S.

"How far should a doctor go? MDs say

they ‘need clarity' on Supreme Court's assisted suicide ruling."

National

Post, 23 February, 2015

(2015-07-04)

8. In a 2014 poll of 5,000 CMA members, 27% of

physicians surveyed said they were willing to participate in assisted

suicide, while 20% were willing to participate in euthanasia. Assuming that

the results can be applied to the whole Association, that indicated about

21,600 physicians available for assisted suicide and 16,000 for euthanasia.

Moore E.

"Doctor is hoping feds will guide on assisted suicide legislation." Edson Leader, 12 February, 2015.

(Accessed 2015-07-16).

9. Ed2-webcast - 15:00-15:22

10. Ed2-webast - 15:23 - 15:39

11. Ed2-webast - 15:42 - 15:51

12. Assuming, (a) that those who would

provide euthanasia or assisted suicide for terminal illness make

up the 10% difference between 19% and 29% of the subset of

willing physicians, and (b) that those willing to provide

euthanasia and assisted suicide for psychological suffering

would also be willing to provide the services for the

non-terminally ill and the terminally ill, though the reverse

would not necessarily hold.

13. Ed2-webcast - 16:50-17:13

14.

https://www.cfpc.ca/uploadedFiles/Health_Policy/_PDFs/ePanel_psa_results_EN.pdf

15. Ed2-webcast - 17:20-17:25.

16. Ed2-webcast - 17:14-17:38.

17. Ed2-webcast - 17:38-17:55.

18. Picard A.

"Less than a third of doctors

willing to aid in assisted dying: CMA poll." Globe and Mail, 25 August,

2015

(Accessed 2015-10-22).

19. Kirkey S.

"Majority of doctors

opposed to participating in assisted death of patients: CMA

survey." National Post, 25 August, 2015.

(Accessed 2015-10-22).

20. Vogel L.

"Many doctors won't provide

assisted dying." CMAJ, 31 August, 2015

(Accessed 2015-10-22).

21. Ed2-webcast - 20:09.

22. Ed2-webcast - 15:53-16:22.

23. Ed2-webcast - 20:09-20:41.

24. Ed2-webcast - 20:41-20:50.

25. Ed2-webcast - 16:22-16:31.

26. Ed2-webcast - 22:29-22:50.

27. Christian Medical and Dental Society,

Doctors'

Group urges Canadian Medical Association to defend conscience rights on

assisted death. News release, 24 August, 2015

(Accessed 2015-10-23)

28. Canadian Medical Association,

148th Council Delegates' Motions -

End-of-life Care

(Accessed 2015-10-23).

29.

148th ' Council Delegates' Motions -

End-of-life Care.

Accessed 2015-10-23

30. Rutka J. "Conscientious objections, referral

for assisted dying prove controversial topics at CMA meeting ." Canadian

Health Care Network, 26 August, 2015

31. Schadenburg A.,

"Canadian Medical Association delegates

rejects conscience rights for physicians with regard to euthanasia."

(Accessed 2015-10-23).

32. Gyapong D.

"Doctors to lose conscience

rights under CMA decision." Western Catholic Reporter, 14 September, 2015

(Accessed 2015-10-23).

33. Canadian Medical Association,

Board of Directors October 2015 Meeting

Highlights (Accessed 2015-10-23)

34. Canadian Medical Association,

Principles-based Recommendations for a Canadian Approach to Assisted

Dying, Foundational Principle 2 (Accessed 2015-11-24).

35. Canadian Medical Association,

Submission to the Federal External Panel

on Options for a Legislative Response to Carter vs. Canada (Federal External

Panel) 19 October, 2015

(Accessed 2015-10-24)

36. Canadian Medical Association,

Principles-based Recommendations for

a Canadian Approach to Assisted Dying (2016) (Accessed 2016-01-09).

37. Board of Directors Meeting: "Therapeutic Abortion Study Major

Association Project: Finance Committee Reports Mild Optimism for Year." CMAJ

Volume 103(11) 1218, November 21, 1970.

(https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1930622/pdf/canmedaj01607-0085.pdf)

Accessed 2015-06-17

38. Murphy S.

"NO MORE CHRISTIAN

DOCTORS, Appendix 'F' - The Difficult Compromise. Canadian Medical

Association, Abortion and Freedom of Conscience." Protection of

Conscience Project

39. College of Physicians and Surgeons of

Ontario,

Professional Obligations and Human Rights (March, 2015)

(Accessed 2015-12-28).

40. Canadian Medical Association,

"Submission to the College of Physicians and Surgeons of Ontario: Consultation on CPSO

Interim Guidance on Physician-Assisted Death"(13 January, 2016)

(Hereinafter "CMA Submission")