The Hippocratic "oath"

(Some further reasonable hypotheses)

Research 2014; 1:733 (25

April, 2014)

Reproduced under

licence

Sergio Musitelli n1,*,

Ilaria Bossi n2,*

Abstract

Although 65 treatises - either preserved or lost, but quoted by ancient

authors like Bacchius (3rd century B.C.), Erotian (1st century A.D.) and

Galen (c. 129-199 A.D.) - are ascribed to Hippocrates (c. 469-c. 399 B.C.)

and consist of nearly 83 books, nonetheless there is no doubt that none of

them was written by Hippocrates himself. This being the fact, we cannot help

agreeing with Ulrich von Wilamowitz Möllendorf (1848-1931), who maintained

that Hippocrates is a name without writings!

Indeed the most of the treatises of the "Corpus hippocraticum" are not

the collection of Hippocrates' works, but were likely the "library" of the

Medical School of Kos. The fact that it contains some treatises that

represent the theories of the Medical school of Cnidos (most probably

founded by a certain Euryphon, almost contemporary with Hippocrates), with

which it seems that Hippocrates entered into a relentless debate, is an

absolute evidence.

Moreover, we must confess that, although Celsus (1st century B.C.-1st

century A.D.) (De medicina, I, Prooemium) writes that "Hippocrates of

Kos…separated this branch of learning (i.e. Medicine) from the study of

philosophy", we have nothing to learn from the hippocratic treatises under

the scientific point of view.

However, whatever its origin, the "Oath" is a real landmark in the ethics

of medicine and we can say - with Thuchydides (460/455-400 B.C.) (Histories,

I, 22, 4) - that it is "an achievement for eternity".

Suffice it to remember that every graduand in Medicine is generally still

bound to take an oath that is a more or less modified and more or less

updated text of the "Hippocratic oath" and that even the modern concept of

bioethics has its very roots in the Hippocratic medical ethics.

"The art is long; life is short; opportunity fleeting; experiment

treacherous; judgment difficult: The physician must be ready, not only to do

his duty himself, but also to secure the co-operation of the patient, of the

attendants and of externals, " says the first "Aphorism" and the latest

author of "Precepts" (chapter VI) writes: "where there is love of man, there

is also love of the art", and the "art" par excellence is medicine! These

precepts go surely back to Hippocrates's moral teaching.

Nonetheless, the preserved text of the marvellous "Oath" raises many

problems. Namely:

1) which is the date of it"?

2) Is it mutilated or

interpolated?

3) Who took the oath, i.e. all the practitioners or only those

belonging to a guild?

4) What binding force had it beyond its moral

sanction"?

5) Last but not least: was it a reality or merely a "counsel of

perfection"?

In this article we have gathered and discussed all the available and most

important sources, but do not presume to have solved all these problems and

confine ourselves to proposing some reasonable hypotheses and letting the

readers evaluate the positive and negative points of our proposals.

Although we must agree with W.H.S. Jones that about the so-called

"Hippocratic Oath", as well as about nearly all the treatises of the "Corpus

Hippocraticum" the honest inquirer can only say that for certain he knows

nothing,[1]

[2] nonetheless we can at least propose some reasonable hypotheses.

There cannot be any doubt that:

1) Hippocrates (469-399 B.C) was an "Asclepiad", i.e. a member of

something like a medical "guild";

2) he trained physicians for a fee, as the following passage of the

platonic dialogue "Protagoras" (311 b-c) proves:

Socrates: Should you want to go to your namesake Hippocrates of Kos, the

member of the guild of the Asclepiads, and to give him money as a fee

and should anyone ask you: "Tell me, Hippocrates, who is the Hippocrates

to whom you are on the point of giving a fee?", what would you answer?

Hippocrates: I would say that he is a physician.

Socrates: In order

to become what?

Hippocrates: A physician!

3) He did not begin teaching any disciple unless he swore an "Oath", as

the following passage of Aristophanes' (c.450-c.385 B.C.) comedy "Thesmophoriazoúsai" (vv. 269-274) proves:

Euripides: Go then!

Mnesìochos: No, by Apollo!, unless you swear!

Euripides: What must I swear?

Mnesìlochos: To save me with all means,

if I would suffer from any damage!

Euripides: Well then! I swear by

the ether, the house of Zeus!

Mnesìlochos: Is it not better to swear

the oath of the guild of Hippocrates?

Euripides: So I swear by all

the supreme Gods!

As Aristophanes' comedy was written and staged in 411 B.C., that is when

Hippocrates was about 58 years old, and therefore at the height of his

activity as both a physician and a master of medicine in Kos, the Greek

comedian could not avoid knowing very well both his behaviour towards his

disciples, the rules of his School and his teaching programme.

As for Plato's (c.429-347 B.C.) statement, one can say the same, because

"Protagoras" is one of his earliest dialogues and therefore it was written

at most few decades after Hippocrates' death, when his Medical School was at

the top of its booming. In this connection it is worth remembering that the

foundation of the great "Asclepieum" of Kos at the middle of the 4th century

B.C. was due largely to disciples of Hippocrates. These being the facts, we

are presented with two problems: is the text of the "Oath" preserved in the

"Corpus hippocraticum" just the original text of the "Oath" requested by

Hippocrates to accept any new disciple in his school?

If not, when and why was it reviewed, corrected and possibly

interpolated?

The extant text reads as followsn3:

1]

I swear by Apollo Physician, by Asclepius, by Health,

2] by Panacea,

and by all the gods and goddesses, making

3] them witnesses that I will

carry out, according to my ability

4] and judgement, this oath and this

indenture. To consider my

5] teacher in this art as equal to my parents;

to make him partner in my

6] livelihood, and when he needs money to

share mine with

7] him; to consider his offspring equal to my brothers;

to teach

8] them his art, if they require to learn it, without any fee

and any

9] covenant; and to impart precepts, oral instruction, and all

10] the other learning to my sons, to the sons of my teacher, and

11] to

disciples, who have signed the indenture and sworn obedience

12] to the

physicians' Law, but to none other. I will use treatment

13] to help the

sick according to my competence and my judgement,

14]

but I will keep away all treatment which is

intended to cause

15] injury or wrong.

I will

not give poison to anyone even if asked

16] to do so. Neither will I

give a pessary to a woman to cause

17] abortion.

But I will guard my life

and my art in purity and in holiness.

18]

I will not use the knife even

on sufferers from stone,

but I will give

19] place to such as are

craftsmen therein. Into whatever house I enter,

20]

I will enter to help

the sick, keeping myself free from all intentional

21] wrong-doing and

harm, and most of all from sexual intercourse

22] with women or men, free

or slave. Whatsoever I see or hear in the

23] course of practice, or even

outside my practice in social intercourse,

24] that ought never to be

published abroad, I will not divulge, but consider

25] such things to be

holy secrets. Now if I keep this oath and break it not,

26] may I enjoy

honour in my life and art, among all men and for all time;

27] but if I

transgress and forswear myself, may the opposite befall me.

It begins (lines 1-5) with the words "I swear by Apollo Physician, by

Asclepius, by Hygeia and Panaceia and all the gods and goddesses, making

them my witnesses, that I will fulfil, according with my ability and

judgement, this oath and this indenture (as Jones translates the Greek word

"syggraphé"), or "this covenant" (as Edelstein translates the same Greek

word)[3]n4

The content of the "indenture / covenant" (lines 5-12) follows this

premise:

to consider my teacher in this art as equal to my parents and to make him

partner in my livelihood, and when he needs money, to share mine with him;

to consider his offspring as equal to my brothers; to teach them this art -

should they desire to learn it - without any fee and any covenant; and to

impart precepts, oral instruction, and all the other learning to my sons, to

the sons of my teacher and to disciples, who have signed the indenture and

have sworn obedience to the physician's Law, but to none other.

This means that a person, who wanted to benefit from the teaching of

Medicine at the school of Kos must first of all "sign" a contract; second

take an "Oath" (or most probably vice versa, as we shall see later which was

just the guild), becoming a member of a restricted group characterized by an

aristocratic exclusivenessn5

[4] of the

"Asclepiadae". As for the "syggraphé"(which literally means "a written contract signed by both the parties", i.e. the future disciple

and the master) it was something like our school enrolment and, at the same

time, something like our school regulation.

On the basis of the order of the words "this oath and this indenture (or

"covenant") one would expect 1) the text of the "Oath"; 2) the text of the "indenture / covenant".

However

A) there is a clear contradiction between "this oath (a) and this

indenture (b)" and the following "who have signed the covenant (b) and have

taken the oath (a)";

B) moreover why the "signature" of an "indenture /

covenant" would follow the initial "I swear by Apollo Physician, etc"? In

fact the real oath does not precede the terms of the "indenture / covenant"

but follows them, as the lines 5-15 concern the "indenture / covenant",

whilst the real commitments (prohibitions and commands) only begin at line

16 and consist of:

- a) a first positive pledge (lines 12-13): "I will use treatment to

help the sick according to my competence and my judgement";

- b) a first prohibition (lines 14-15): "I will keep away all

treatment which is intended to cause injury or wrong";

- c) a second prohibition (line 15): "I will not give poison to

anyone";

- d) a third prohibition (lines 15-16): " [I will not give poison]

even if asked to do so";

- e) a fourth prohibition (lines 16-17): "I will not give a pessary to

a woman to cause abortion";

- f) a second positive pledge (line 17): "I will guard my life and my

art in purity and in holiness";

- g) a fifth prohibition (line18 ) : "I will not use the knife, eve,

on sufferers from stone";

- h) a first particular command (lines 18-19): "I will give place to

such as are craftsmen therein";

- i) a second particular command (line 20): "I will enter to help the

sick";

- j) a third particular command (lines 20-22): "I will keep myself

free from all intentional wrong-doing and harm, and most of all from

sexual intercourse with women or men, free or slave";

- k) a fourth particular command (lines 22-25): "I will not divulge" "whatsoever I see or hear in the course of practice , or even outside my

practice in social intercourse...consider such things to be holy

secrets";

- l) a final vow (lines 25-27): "If I keep this oath and break it not

it, may I enjoy honour in my life an art among all men and for all time;

but if I transgress it and forswear myself may the opposite befall me

As everybody sees, four prohibitions follow the first positive pledge and

four particular commands follow the second one.

This being the fact, the fifth prohibition concerning the "use of the

knife" on the one hand is absolutely out of place and does not correspond to

a fifth particular command; on the other hand one would expect it not after

the second pledge but before it, as well as one would obviously expect a

fifth particular command corresponding to this fifth prohibition. But we

shall deal with it later.

At any rate Aristophanes' words "I swear by all the supreme Gods" seem

something like a summary (or an abbreviated paraphrase) of the first lines

of our text, and mainly seem repeating the entry "I swear...by all the Gods

and Goddesses making them witnesses".

Therefore the legitimate suspicion arises that

A) these first lines ("I

swear by Apollo...that will carry out, according to my ability and judgement

this oath") represent the "introduction" to the real "Oath";

B) "and this

indenture" is a later interpolation inserted into it when the "indenture"

itself was joined with it;

C) the original text of the "Oath" was most

probably: "I swear by Apollo...and by all the Gods and Goddesses...that I

will use treatment to help the sick,... holding such things to be holy

secrets", followed (as in many of our prayers) by the final vow: "if I carry

out this oath, and break it not, may I gain forever reputation among all men

for my life and for my art; if I transgress it and forswear myself, may the

opposite befall me", which seems approximately corresponding to our "Amen /

So be it".

We cannot be sure whether was the "indenture / covenant" signed before or

after taking the "Oath", but can reasonably suppose that

- one thing was the "indenture / covenant", and quite another thing

was the "Oath"

- most probably the novice was asked to take the "Oath" before signing

the "written contract" and therefore before becoming a fully entitled

member of the guild of the "Asclepiads".

At this point we can confidently answer to the first question:

1) the

extant text of the so-called "Hippocratic oath" isn't at all the original

one!

2) It is the result first of all of the insertion of the text of the "indenture - covenant" into the original

"Oath";

33) there cannot be any

reasonable doubt that the prohibition of "using the knife" is a very late

interpolation, as maintained by Jones and by us in two former articles

n6

[6]

[7], all the more so because the command :

"I will give place to such as

are craftsmen therein" is clearly alluding to specialized "lithotomists",

whom none of the hippocratic treatises deal with and Celsus' passages in De

Medicina, VII (26, 3, B in particular) do not speak about "specialized

lithotomists" prior to Ammonius (or Hammonius), who lived and was active in

the III century B.C., that is to say during the great Hellenistic period.

Moreover the "Prooemium" of book VII proves that Celsus himself thought that

"surgery" - which he calls "the third part of the Art of Medicine" - was a

very recent "specialization" that started just in the Hellenistic period. In

fact after having quoted Hippocrates as if it were a sort of "historical

duty", he writes:

Later it was separated from the rest of medicine, and began to have its

own professors; in Egypt it grew especially by the influence of

Philoxenus (flourished in Alexandria in the 1st century B.C.), who wrote

a careful and comprehensive work on it in several volumes, Gorgias

(flourished in Alexandria in the 3rd century B.C.) and Sostratus

(flourished in Alexandria in the 1st century B.C.)and Heron (flourished

in Alexandria in the 3rd century B.C.) and the two Apollonii (flourished

in Alexandria in the 3rd - 2nd century B.C.) and many other celebrated

men, each found out something.

It is clear that Celsus is implying that the real "History of Surgery"

started only with the Alexandrian school of medicine, which flourished just

from the 3rd century B.C.! All the more so because he confines himself to

quoting some of the "surgical" treatises of the Corpus hippocraticum (Head

wounds, Surgery, Fractures, Joints, Mochlikon) - that is to say treatises

dealing with fractures and orthopaedic surgery - in the 8th book just at the

beginning of which Celsus states that

The remaining part of my work relates to the bones; and to make this

more easily understood, I will begin by pointing out their position and

shapes and tells nothing at all about urological surgery!

A reasonable answer to the second question (when and why was it reviewed,

corrected and possibly mended?) needs at least three important premises.

First of all neither Plato, nor Aristotle (384-322 B.C.) asked the

disciples of the Academy and the Lyceum (that can be considered the

ancestors of our Universities) either to sign any "indenture - covenant" or

to take any "Oath", let alone to pay any fee. Neither any disciple of the

Alexandrian Museum (the first real University in the modern sense of the

word [5] ) was ever asked the signature of an indenture or the taking of any

"Oath", or the payment of any fee. Galen (c.129-199 A.D.) states that he

studied anatomy at the famous Medical School of Alexandria and urges the

novices to go to Alexandria to study anatomyn8, but never speaks

of either an "indenture" to be signed, or an Oath to be taken, let alone of

any fee to be paid. In fact the about 100 research scholars and teachers

housed in the Museum were supported by generous salaries granted first by

the Ptolemies, then by the Roman emperors and therefore they could easily,

or better they must teach for free.

Second: it seems likely that none of the books of the so-called "Corpus

hippocraticum" is to be ascribed to Hippocrates himself. It is rather

probable that the writings came to Alexandria as the remnants of medical

literature which had circulated in the fifth and fourth centuries as

anonymous works, like technical literature commonly was in that era./p>

Third: although Erotian (a grammarian and physician, who flourished in

the age of the emperor Nero (54-68 A.D.) in his "Hipporatic glossary"

admitted the "Oath" to be genuinely Hippocratic, neither Celsus (1st century

B.C.-1st century A.D.) nor Galen ever quote or refer to it, although

Aristophanes' passage quoted above makes sure that an "Oath" had to be taken

by those, who wanted to join the Medical School of Kos. After having taken

the "Oath" the disciple had to sign the "indenture-covenant".

Well then: as the Alexandrian scholars knew that no "indenture-covenant"

was requested to any disciple at their times (and - as said above - since

Plato and Aristotle), it is likely that they considered the text as a

fragment of the "Oath" and therefore inserted it just at the beginning, as

well as they added books II, IV, V, and VI of the treatise "Epidemics" to

the original books I and III, not to say a lot of more or less ample works

that are surely spurious

[8]. But we think that it is worth observing that although more or less

abbreviated Latin translations of the "Oath" can be found in a lot of

mediaeval manuscripts [9], in all of them both the text of the

"indenture-covenant" and the

prohibition of "using the knife" are missing, few Latin manuscripts and a

printed edition of their text excluded, as we shall state later.

WWe agree with H.E.Sigerist and W.H.S. Jones

n10 that the first

gap may be due to the fact that the aristocratic exclusiveness its text

represented was in sharp contrast with the Christian idea of universal

brotherhood.

As for the second we must confess that it is rather astonishing: why the

prohibition of "using the knife" could ever be eliminated in a period when

the final divorce of "Medicine" from "Surgery" had taken place at least

since the 5th, not to say - on the basis of one of Galen's statements -

since the 2nd century A.D.? In fact Galen maintains in "De medendi methodo"

(On therapeutic method), VI, 2, K, X, 454-455 that:

mmust know the doctrines that teach us which is the

human nature, which are its particular qualities, which is unhealthy

state of the humours, and which is plethora; moreover he must be able to

distinguish acute and dull senses; and which may be the suitable

medicaments according to the nature of each patient; when he must have

recourse immediately to coagulants in case of fresh wounds and when to

other kinds of medicaments. Thessalus of Tralles († 79 A.D.)

n9

neglected all this previous knowledge and revealed his puerility and his

ignorance by relying on what even the populace knows. Indeed knowing

what must be done is not important; it is important knowing how it must

be done! However it seems that Thessalus ignores everything and while he

thought that every bloody wound was to be treated by the same method, he

smeared a pierced nerve with the drug he had often had a successful

recourse to in cases of very severe wounds. By contrast he caused the

formation of a phlegmon and undertook its treatment by a poultice made

of wheat flour. The result was that the wound became gangrenous and he

murdered this as well as many other patients in the space of six days.

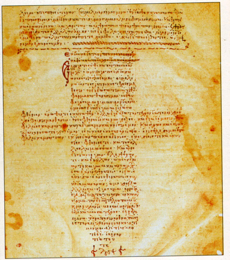

Figure 1.

We think that it is possible that the mediaeval authors had at their

disposal a text of the "Oath" where this prohibition was still missing.

However the legitimate suspicion arises that it was still present at least

in one of the Greek manuscripts, whose text was the same we read today,

because the prohibition of "using the knife" and the command of "giving

place to such as are craftsmen therein" is still present in 5 Latin

manuscripts n7 containing a Latin translation of the Oath made by

Niccolò Perotto (1429-1480)n11 and printed in Basel in 1538, as

well as in the Arab translation by Ibn abī Uşaybi 'ah (1203/1204-1269/1270),

whilst it is already missing in the Greek cross-shaped text of the Vaticanus

Urbinates 64 (fol. 116) (Fig. 1), of the Ambrosianus B 113 sup. (fol. 203)

and of the Bononiensis 3632.

In this connection it is worth observing that all the authors of surgical

treatises, from Lanfrancus of Milan († c.1315) to Fabricius Hildanus

(1560-1634) recommend the surgeon to have recourse to the advice of a

"physician" in cases of exceptionally dangerous and risky surgeries.

On the contrary the insertion of the text of the "indenture - covenant"

goes most probably back at least to a period between the second half of the

3rd and the 2nd century B.C., i.e. when the "Corpus Hippocraticum" formed

and it too was eliminated in Christian times, i.e. between the 4th and the

5th century A.D. for the above mentioned motives.

Conclusion

We are well aware that these are nothing but hypotheses. Nonetheless we

believe that they may be considered as supported enough by both internal and

external evidences, although we cannot avoid agreeing with Jones that "the

interest of the "Oath" does not lie in its baffling problems" and that

although "these may never be solved... the little document is nevertheless a

priceless possession. Here we have committed to writing those noble rules,

loyal obedience to which has raised the calling of a physician to be the

highest of all the professions".

Notes

1. - History Office, European Association of Urology. I dedicate also this

article to the memory of my adored son Giulio, who was killed y a criminal

river, who did not observe a STOP sign, on 14/05/2012.

2. - MD University of Milan - Casualty Ward and Emergency Medicine -

St.Anna Hospital, Como, Italy

3. - We quote the lines of the Greek text of Jones' edition. Cf. reference

n. 1

4. - We feel bound to express our gratitude to Prof. Dr. Rainer Engel, who

has let us have Jones' and Edelstein's fundamental contributions at our

disposal.

5. - Cf. H. E. Sigerist, A History of Medicine, New York, Oxford Unversity

Press, 1961, II, p. 304.

6. - Cf. W.H.S. Jones, Hippocrates, etc (cf. reference n. 1); I, 296; S.

Musitelli, Comment on the article "Operative Urology and the Hippocratic

Oath", in De Historia Urologiae Europaeae Drukkerij Gelderland, Arnhem, IX

(2002), p. 163 ff.; S. Musitelli & J.F. Felderhof, Castration from

Mesopotamia to the XVI century, in De Historia Urologiae Europaeae ,

Drukkerij Gelderland, Arnhem, X (2003), p. 112 ff.

7. - Laurentianus 73,40 ; Leydensis B.P.L. 156; Bernensis 131;

Vindobonensis 4772 and Basileensis E III 15.

8. - Cf. Anatomicae admnistratuiones (Anatomical procedures), I, 2, K. II,

220

9. - He was the founder of the School of the so-called "Methodists"

10. - Cf. H. E. Sigerist, A History of Medicine, etc. II, 304; W.H.S.

Jones, The Doctor's Oath, etc. Cambridge, 1924, p. 23.

11. - The text has been, so to say, "Christianized": in the Latin

translations the pagan Gods have disappeared and the first lines read as

follows: "From the Oath according to Hippocrates in so far as a Christian my

swear it. Blessed God the Father of our Lord Jesus Christ, who is blessed

for ever and ever. I lie not". Cf. Hippocrtes, etc, I, 296.

References

[1.]

"Hippocrates with an English translation by W.H. Jones, William

Heinemann ltd, London - Harvard University Press, Cambridge

Massachusetts, 1957, I, 291.

[2.]

W. H. S. Jones, The Doctor's Oath - An essay in the History of

Medicine, Cambridge, at the University Press, 1924.

[3.]

L. Edelstein, The Hippocratic Oath, Baltimore, The John Opkins

Press, 1943.

[4.]

H.E. Sigerist, A History of Medicine, New York, Oxford

University Press, 1961, II, p.304.

[5.]

S. Musitelli, The first Universities, in Europe - the cradle of

Urology, History Office of the European Association of Urology,

Arnhem, 2010.

[6.]

S. Musitelli: Comment to the article "Operative Urology and the

Hippocratic Oath" in De Historia Urologiae Europaeae, Drukkerij

Gelderland, Arnhem, IX (2002), 163 ff.

[7.]

S. Musitelli & J.F. Felderhof: Castration from Mesopotamia to

the XVI century, in De Historia Urologiae Europaeae, Drukkerij

Gelderland, Arnhem, X (2003), 112 ff.

[8.]

L. Edelstein, in The Oxford Classical Dictionary, Oxford, at the

Clarendon Press, 1953, entry Hippocrates.

[9.]

Cf. S. Musitelli, Hippocratic Oath during the Middle Ages, in

IHFK Bulletin, Vol.3, 1994, p. 3 ff.