Entrenching a 'duty to do wrong' in medicine

Canadian government funds project to suppress freedom of

conscience and religion in health care

Full Text

Click to enlarge

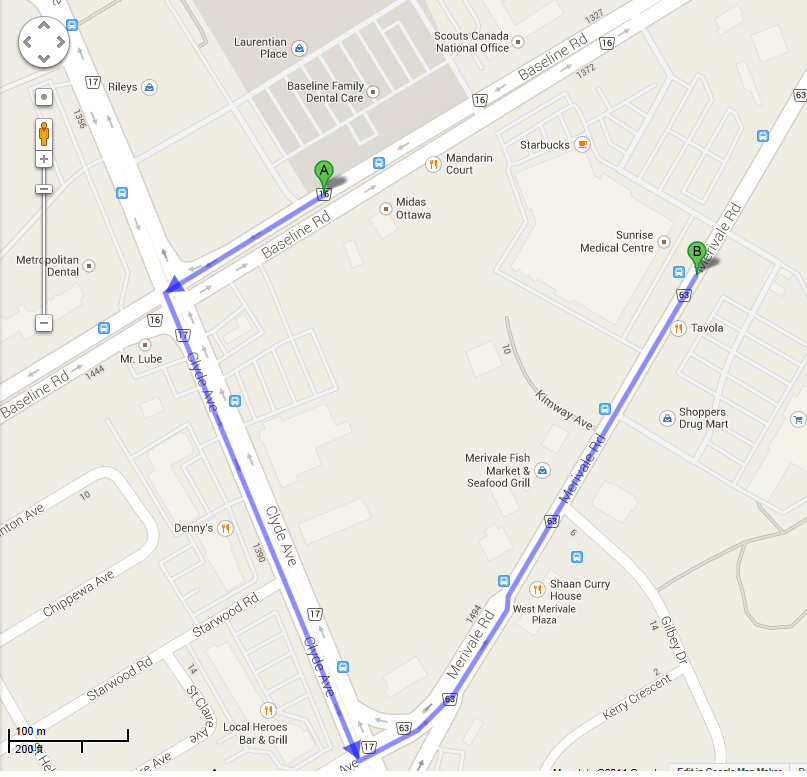

Click to enlarge A 25 year old woman who went to an Ottawa walk-in clinic

(A) for a birth

control prescription was told that the physician offered only Natural Family

Planning and did not prescribe or refer for contraceptives or related

services. She was given a letter explaining that his practice reflected his

"medical judgment" and "professional ethical concerns and religious values."

She obtained her prescription at another clinic about two minutes away (B) and

posted the physician's letter on Facebook. The resulting crusade against the

physician and two like-minded colleagues spilled into mainstream media

1 and

earned a blog posting by Professor Carolyn McLeod on

Impact Ethics.2

Professor McLeod objects to the physicians' practice for three reasons.

First: it implies - falsely, in her view - that there are medical reasons to

prefer natural family planning to manufactured contraceptives. Second, she

claims that refusing to refer for contraceptives and abortions violates a

purported "right" of access to legal services. Third, she insists that the

physician should have met the patient to explain himself, and then helped

her to obtain contraception elsewhere by referral. Along the way, she

criticizes Dr. Jeff Blackmer of the Canadian Medical Association (CMA) for

failing to denounce the idea that valid medical judgement could provide

reasons to refuse to prescribe contraceptives.

However, the formation of medical judgement involves more than just

signing on to a current majority opinion; there is still room in the medical

profession for critical thinking.3 The CMA acknowledges the possibility of

divergent professional opinions; that is why its Code of Ethics

requires physicians to advise patients if their views are not representative

of those of the profession as a whole.4 Perhaps Dr. Blackmer refrained from

comment on the physician's medical judgement because, like Professor McLeod,

he did not know the basis for it, and was thus hardly in a position to offer

an informed opinion.

As Professor McLeod suggests, a face-to-face meeting with patients is

normally preferable, and many physicians who will not facilitate abortion

nonetheless believe they should meet with women who want one. On the other

hand, as evidenced by a Facebook comment, walk-in clinic patients who want

The Pill may well be angered if, after "waiting the customary two hours, "

the physician does not provide it.5 Thus, it may actually be preferable for

a receptionist to notify walk-in clinic patients promptly when they arrive.

Unfortunately, no single solution is likely to consistently strike the right

balance between personal interaction and patient convenience or preferences.

Professor McLeod warns that physician freedom to act on moral or

religious beliefs is limited, explaining that, if it were not, Muslim

physicians would refuse to accept female patients, and Catholic physicians

would deny care to women who have had previous abortions. These assertions

are surprising - and erroneous. In fact, Muslim physicians may treat

patients of the opposite sex,6 and a previous abortion is morally irrelevant

to treatment decisions by Catholic physicians.7 Her suggestion that the

religious beliefs of Muslim or Catholic physicians would make them

"uncomfortable" in such circumstances bespeaks a complete lack of

intellectual engagement with Islamic medical ethics and with Catholic moral

theology. There is a significant difference between discomfort that might

arise in real circumstances of ethical conflict, and principled and rational

decision making based on religious or moral convictions.

Finally, her claim that physicians "cannot act on moral beliefs that

prevent them from providing referrals for standard services" - by which she

means contraception and abortion - is contradicted by Canadian Medical

Association policy8 and by a statement of the 25,000 member Ontario Medical

Association (OMA): "We believe that it should never be professional

misconduct for an Ontarian physician to act in accordance with his or her

religious or moral beliefs."9

Nonetheless, a central goal of Professor McLeod's

Canadian Institutes of

Health Research (CIHR) funded project10 is to entrench in medical

practice a duty to refer for or otherwise facilitate morally contested

procedures. From the perspective of many objecting physicians, this amounts

to imposing a duty to do what they believe to be wrong. Two other leaders of

this project - Jocelyn Downie and Daniel Weinstock - insist that objecting

physicians also be forced to refer for euthanasia and assisted suicide, for

precisely the same reasons that Professor McLeod gives for compulsory

referral for abortion and contraception.11 Coincidentally, a third

collaborator on the McLeod project is François Baylis, the editor of Impact

Ethics - and both Jocelyn Downie and François Baylis are members of the CIHR

funded Novel Tech Ethics research team that publishes Impact Ethics.12

That the state can legitimately compel people to do what they believe to

be wrong and punish them if they refuse is a dangerous idea that turns

foundational ethical principles upside down. The inversion is troubling,

since "a duty to do what is wrong" is being advanced by those who support

the "war on terror." They argue that there is, indeed, a duty to do what is

wrong, and that this includes a duty to kill non-combatants and to torture

terrorist suspects.13

CMA and OMA policy on freedom of conscience safeguards the legitimate

autonomy of patients and the integrity of physicians. The policy also

protects the community against a particularly deadly form of

authoritarianism: a demand that physicians kill their patients or help to

arrange for the killing, even if they believe doing so is wrong.

Notes:

1. Murphy S.,

"'NO MORE CHRISTIAN

DOCTORS'- Part 1: The making of a story." Protection of

Conscience Project, 25 February, 2014.

2. McLeod C.

"The Denial of 'Artificial' Contraception by Ottawa Doctors."

Impact Ethics, 4 March, 2014

(Accessed 2014-03-13)

3. Murphy S.,

"'NO MORE CHRISTIAN

DOCTORS'- Part 2: Medical judgement and professional ethical

concerns." Protection of Conscience Project, 25

February, 2014.

4. Canadian Medical Association

Code of Ethics (2004): "45. Recognize a responsibility to give

generally held opinions of the profession when interpreting scientific

knowledge to the public; when presenting an opinion that is contrary to

the generally held opinion of the profession, so indicate." (Accessed

2014-02-22)

5.

K__N__H__. 30 January, 2014, 11:48 am

6. Hathout H. Islamic Perspectives in

Obstetrics and Gynaecology. Kuwait: Islamic Organization for

Medical Sciences, 1986, p. 161-166. Islamic Medical Association of North

America,

Islamic Medical Ethics: The IMANA Perspective, p. 11. (Accessed

2014-03-14). McLean M. Conscientious objection by Muslim students

startling. J Med Ethics November 2013 Vol. 39 No. 11.

7. For example: "46. Catholic health care

providers should be ready to offer compassionate physical,

psychological, moral, and spiritual care to those persons who have

suffered from the trauma of abortion."

Ethical and Religious Directives for Catholic Health Care Services

(5th ed.) United States Conference of Catholic Bishops, 17

November, 2009. (Accessed 2014-03-16). John Paul II,

Encyclical

Evangelium Vitae (25 March, 1995), 99.

(Accessed 2014-03-14); Project Rachel Ministry

(Accessed 2014-03-14)

8. Murphy S.

"'NO MORE CHRISTIAN

DOCTORS, Appendix 'F.' The difficult compromise: Canadian Medical

Association, Abortion and Freedom of Conscience." Protection of

Conscience Project, 25 February, 2014

9. OMA Urges CPSO to Abandon Draft Policy

on Physicians and the Ontario Human Rights Code. OMA President's Update,

Volume 13, No. 23 September 12, 2008. OMA Response to CPSO Draft Policy

"Physicians and the Ontario Human Rights Code." Statement of the Ontario

Medical Association, 11 September, 2008.

10.

Let their conscience be their guide?

Conscientious refusals in reproductive health care.

(Accessed 2014-03-07)

11. Murphy S.

"'NO MORE CHRISTIAN

DOCTORS'- Part 5: Crossing the threshold." Protection of Conscience

Project, 25 February, 2014

12. Impact Ethics,

NTE team.

(Accessed 2014-03-16)

13. Gardner J. Complicity and Causality, 1

Crim. Law & Phil. 127, 129 (2007). Cited in Haque, A.A.

"Torture,

Terror, and the Inversion of Moral Principle." New Criminal Law Review,

Vol. 10, No. 4, pp. 613-657, 2007; Workshop: Criminal Law, Terrorism,

and the State of Emergency, May 2007. (Accessed 2014-02-19)